–I found a relic in the dawn

Set idol as wallpaper. Wait. Busy in museum. Haunting the glass like I was there.

In many ways that September was a weird, in-between, month. I’d just finished and handed in my Master’s dissertation on transfeminist poetics and, in so doing, had reached the end of my four years in university education. Incidentally, the hand-in date for my final dissertation fell on the same day as the psychological evaluation with my gender psychologist that I’d been waiting for for eight months.

24th August. After receiving the diagnosis and handing in the dissertation which had engulfed my life since June, I caught a number 46 bus from my flat near Hampstead to Bloomsbury for drinks at Elliot’s house. Two enormous things had coincided, chimed together.

The air in the bus was electric as we passed over the smooth new roads down the side of St Pancras.

Brekekekek coax coax we are passing under the Seine

So September was the month when I’d finished uni, finished my dissertation, and was waiting for my endocrinologist appointment to get on hormones in October. I was also moving flats and starting a new chapter of my life in south London.

Things were starting to seem possible. My hair, which I’d been growing out for over a year, was almost shoulder length.

In the middle of this slack of time I went to the ‘Feminine Power’ exhibition at the British Museum and at 11:03 took a picture of a sculpture which is the subject of this post:

The sculpture, as listed on the British Museum’s website, is described as follows:

Marble figure of a woman – Spedos type. Proportions very flat and shoulders very broad, but the breasts are in higher relief and the abdomen slightly protuberant. The legs are more rounded and separated by a deep groove. The vulva triangle is lightly grooved. At the back, a spinal groove running down and deepened between the legs; the pelvis is more prominent. The head is of the usual Cycladic type, bent back and thin, with long narrow nose.

The piece, of all the other pieces in the exhibition, stood out to me. It came from the Cyclades, a collection of Islands in the Aegean Sea which now form a part of Greece, and is dated to around 2500BC-2300BC.

To this day, the moment where I stood in front of this sculpture feels like a significant rendezvous. That our two paths could cross: me, a recently out trans girl nervously about to embark upon medical transition, and a Cycladic sculpture of a woman with very broad shoulders from over 4000 years ago.

Indeed, perhaps more than anything else, it was the silhouette of this sculpture that I found so interesting. Her shoulders are huge. I stood, reflected in the glass behind her.

Some context: of all of the things I’m dysphoric about, by far my sorest insecurity is my torso. I have, since the age of around 14 or 15, had had very broad shoulders and big rib cage which make it very difficult to have a cis-looking silhouette. I cannot overstate the amount of pain this has caused me over the years, particularly in 2022, when the continual revelation of the limits my body placed upon the potentialities for my future transition led me to many periods of quiet despair.

Why did this sculpture of a woman, from 4000 years ago, have a silhouette just like mine? And, most importantly, what did this mean for my capacity to live as, and be perceived as a woman?

I stood there, reflected, a gleaming daughter in the busy exhibition. The noise dimmed, and something passed between us.

It was a kind of trans-temporal reckoning, as message received between worlds. Across continents. In the hot dry overgrowth of the Cyclades: my stone mother.

You see, as a trans person, I have very rarely felt like I could identify myself with history, or, indeed, to place myself in a historical narrative upon which I could develop a vision of my future. Medical transitions like the one I am currently undergoing have only really been around for 100 years, so it can be difficult to find the universalised ancestors that so many other communities enjoy.

It’s for this reason that I found Emma Heaney’s book, The New Woman: Literary Modernism, Queer Theory, and the Trans Feminine Allegory to be one of the most enlightening and affirming pieces of scholarship I have ever read for its conviction that transfemininity has its own history as distinct from cis womanhood and male homosexuality.

While medical transitions are generally modern there is a great deal of evidence that trans femininity existed through various practices of social transition, the acknowledgement of a distinct gender for trans feminine people, or even castration techniques used to achieve something approaching what HRT does to the body.

I know I would’ve chopped my balls off on a Greek Island and devoted myself to Paganism… were I given the chance.

So, like Heaney’s book, the sculpture seemed to present to me a new potentiality for my own corporeal existence as it gestated in my pre HRT brain. I saw a place opening up for myself. A thicket. A shaded space in the Cyclades thousands of years ago.

In a society where our bodies are being increasingly policed and tested against cis and heteronormative ideations, (in bathrooms, sports) I think that the creation of new possibilities for lives to be lived is a truly good thing.

It’s not even that I believe that the sculpture is portraying a trans woman. Though, there is that ambiguity. More tangibly it meant that to be a woman in history made no requirement upon my shoulders to be any narrower than hers are.

More recently, the memory of this event has given me another, perhaps more important revelation about the way I see myself.

I realised that, in 2022, the year I came out and began to transition, I had assumed an array of visual hermeneutic practices- ways of interpreting my body- that aimed to soften the blow of dysphoria that hit me when I tried on new clothes or looked in the mirror.

This was the year I finally started to buy the things I’d always wanted to own. The things I had scrolled by on Asos aged 18 but never allowed myself to buy.

But, I quickly found that when I wore these items they didn’t give me the ecstatic weightless joy I had attributed to them all my life. I didn’t look like the models. Worse, so out of proportion was the upper half of my body, particularly my shoulders and ribs, that I would often look freakish and lumbering the mirror.

The straight-on pose of the sculpture would, of all poses, be the one I would avoid most virulently. This is the pose that would render my maleness most hideously apparent.

So, over time I subconsciously developed a set of visual augmentations and occlusions which generally involved a cropping wherein I would only look at a very specific part of my body in a mirror at any given time.

I would, for example, upon trying on a new pair of tights, look at my calves in the full length mirror in my room, usually only from the left hand side, but never my full body for fear that it would throw off of what precious little joy I could feel in this vulnerable time.

I would, and still do, look at my top half in the mirror only if I bring my face within a few inches of its surface so as to obscure my shoulders.

It is only recently, that being May of 2023, that I have begun to notice that these techniques which I had developed in order to diminish my dysphoria were actually working against me.

In fact, the visual cutting I had adopted were themselves a decedent from a common misogynistic visual and poetic trope. The blazon, of course, is a form of lyric poem in which the assumed male speaker lyrically dissects and dismembers the female body into an assortment of literary approximations, flourishes and ideations. Eyes like the sun. Hair like a river. Whatever.

Had I, in recognising my womanhood yet vying to conceal the corporeal limitations that excluded me from cisness, inadvertently performed a misogynistic mutilation of my own body into parts, pieces, attributes, rather than a living breathing whole?

The short answer is: I don’t know. In future, as my confidence grows, I’m going to try to address this. I find that, as my body changes, my facial structure, my complexion, I find it easier to look at myself, to catch a glimpse off guard. To be clear, I have a very long way to go in this regard, and still seldom look in a mirror unless my face is near pressed against the glass, or put on makeup and an outfit that I know minimises the wacky, non-cis proportions of my upper body.

Over the past year I’ve learned a great deal about the types of clothes I can wear, and how I need to wear them. As a general rule, I’ve been feeling a lot better these past two months than I have in a long, long time.

A happy result of this is that with this new-found confidence I’ve felt ready once again to spend some time thinking about how my transness, and more particularly my transfeminitiy- my desire to be and live as a girl- has been inscribed into the way I perceive, interpret and interact with the world- which is the central objective of this collection of writings as a whole. To find out how my transness, which I now see to be the purest form of my being, the cleanest and best part of me, is written into the confusions and occlusions of my psychic life.

Because, life can be so hard to understand when you want so desperately to envision a potentiality in which you could be a girl. In my case, my wanting to be a girl primarily existed as hidden around the edges of my vicarious enjoyment seeing of other women living as women.

I imagine it: hidden in the shaded undersides of innumerable instances.

Take this as an example. In the heady, sunny days after finishing our final third year exams in Cambridge, my friendship group decided to go swimming in the Jesus Green Lido.

It was the 8th of July 2021. In these days I spent almost all my time with my closest friend, Molly, who lived just across the hall from me. That morning Molly realised that she didn’t have anything to wear to go swimming in.

As we walked into central Cambridge to buy her a last-minute swimsuit, I felt a notable excitement. Maybe it was just the sun being out, but things that morning seemed to be in brighter colours as we left Magdalene and arrived at the big Sports Direct in the centre of town.

She picked out the cheapest thing they had, which was a black slazenger one-piece that cost around £9. I was quietly excited. I didn’t even realise it at the time, but, in that moment, I was doing perhaps the one thing I had always wanted to do: go and buy a swimsuit and for that to be the most normal thing in the world.

I didn’t let this on. In fact this blog is probably the first time I’ve ever even formalised or expressed this desire. We walked back; I concealed my excitement. At the time I was living as an out gay man, spending all my time with my wonderful lesbian best friend, and putting a great deal of energy into concealing my trans desire- particularly from Molly.

I took a lot of vicarious transfeminine enjoyment from Molly, and the way she lived her life- the way I couldn’t. I felt bad for it and kept it even from myself. Some nights I’d just go quiet, and clearly be upset. Molly didn’t know what it was. Nor did I. But it was me coming to the limit of my vicarious life. It was the sound of the dream breaking.

Concealing my transness, and having to covet her cisness. It got in the way of what is otherwise probably the most meaningful, intense and wonderful friendship I’ve ever had.

We got back to college. When the time came to get ready to go swimming we split into out separate rooms which, I now realise, stood in for proxy gendered changing rooms. Mine, the sad, male room where I pulled my trunks on, pulled a baggy t shirt and jeans over the top, and Molly’s, filled with the watery light of early July, where she was doing the thing I had always dreamed of, and not thinking a thing of it. Masquerading as normality.

I quickly changed into my trunks before walking over to Molly’s room. The suit was too small she said, as she adjusted the tight straps over the shoulders.

I was excited, delighted to feel this proximity to an experience which had been totally closed off to me. Molly stood there, annoyed that the swimsuit was too small.

She put on the cheap goggles she’d also bought that day and pulled a glum face. It was funny. I asked to take a picture. It was 13:27pm:

Here she was, vaguely inconvenienced, and totally unaware of what was going on in my world. What to her had been a totally normal experience of getting ready to go swimming had for me been an ecstatic window into a vicarious cis existence.

It is in these terms that I imagine my trans femininity- in these kinds of undersides, like round the sunny rim of a pot, my trans eros hidden under a veil of cis normalcy. Slinking in the mirror.

Now, I recognise that one of the most attractive aspects of my staccato living-as-a-girl-but-only-vicariously-in-bright-moments-of-potentiality was that in this hidden world of attribution and desire I was in no way limited by my male body. In fact, in this world, as in my dreams, I had no body at all.

Even in the picture of Molly, where I have cropped myself out, I’m reflected in the mirror, almost invisible, trying to erase myself, to get so close in proximity to her that my maleness vanishes.

She could wear a swimsuit and not look like a freak. She could do it all and just feel normal. Annoyed even. But for me, with my huge shoulders and lumbering rib cage, it wouldn’t have felt normal. Rather than liberating me, it would simply have served to remind myself of the gap between myself and the life I wanted.

I cannot overstate how instances like these form a core part of my phenomenology.

So, I avoid looking in the mirror. Why? because each of these visual reckonings represents testing of my own capacity for futurity. Each time was a testing of the hypothesis: can I be happy and trans? When Molly did it there was no test on me at all, I didn’t need to be involved, and thus, couldn’t be found wanting.

Of all the aspects of female life I had wanted to be a part of, for me, wearing a one-piece swimsuit and for that to be normal, not weird, not sexual, just natural, has sometimes come to feel like it represents a archetype of triumphant victory- everything I ever wanted to do, and everything I couldn’t.

The sculpture released some of this possibility. Where in the picture of Molly from 2021 I had had to be a non-entity, a photographic absence on the borders of cis experience, doting over the friend I loved the most, the sculpture seemed to speak of a future in which I could live authentically as myself and not solely through the lives of others.

My relationship to femininity shown in the picture of Molly is precisely that which animates the entirety of my early pieces of writing: Sunset Sex with Bailey Jay, a poem in which I inhabit a poetic absence around the edges of Bailey’s life- doting on her, unable to myself exist corporeally.

It helps that I’m also going to Greece this summer.

Being on holiday. Walking around in a one piece and having nothing- no bulge- to signal the maleness I wanted to shed. Perhaps unsurprisingly, in picking the swimsuit as its archetypal test, my subconscious had set myself a formidable challenge. And perhaps that was why I had always coveted it: in a one piece, there is nowhere to hide or conceal. You can only be yourself, and be proud of it.

The swimsuit seemed to mean everything, to fulfil every criteria to which I had ever attributed admiration: summer, block colours, minimalism, a certain austerity, tightness, lightness, free mobility, not having a dick.

Where in my previous collections of poetry I had attempted to describe, and in so doing, bring into being warm mediterranean landscapes in which I could exist as an ethereal entity surrounded by indescribable and yet quotidian beauty, I’m now trying to imagine worlds like the one the sculpture shows me. Ones where I can exist. With my closest friends, and loved ones, rather than trembling on the edges of their existence.

For most of the period of its production, my previous collection of poetry, Swimming Pool, Tennis Court, especially its title poems, represented a dismissal and disavowal of my transness and of experiences like the one I described with Molly.

Instead, the collection tried to envision a homoeroticised semi-Grecian landscape in which I could explore my attraction to men divorced from my own body. Where I could haunt the sunny hillside, unseen, and think about what kinds of men I might want to go out with.

Now I want to think of a world where I can exist. And that little statue made one flicker on the horizon.

I took this picture this week on the way to work.

When I look at the white facade of the building in the morning light it vanishes into ideation. Into ideas.

Transversely, it is coming into the actual, trembling over the threshold of morning actuality.

In recognising both my transness and womanhood I’ve had to abandon all my Modernist notions of religiosity that had previously given me great comfort. But, where Hegel presents a transcendent vision of unity, I now see a whole lot of male arrogance and a silence over any experience that falls outside of cis white heteronormativity.

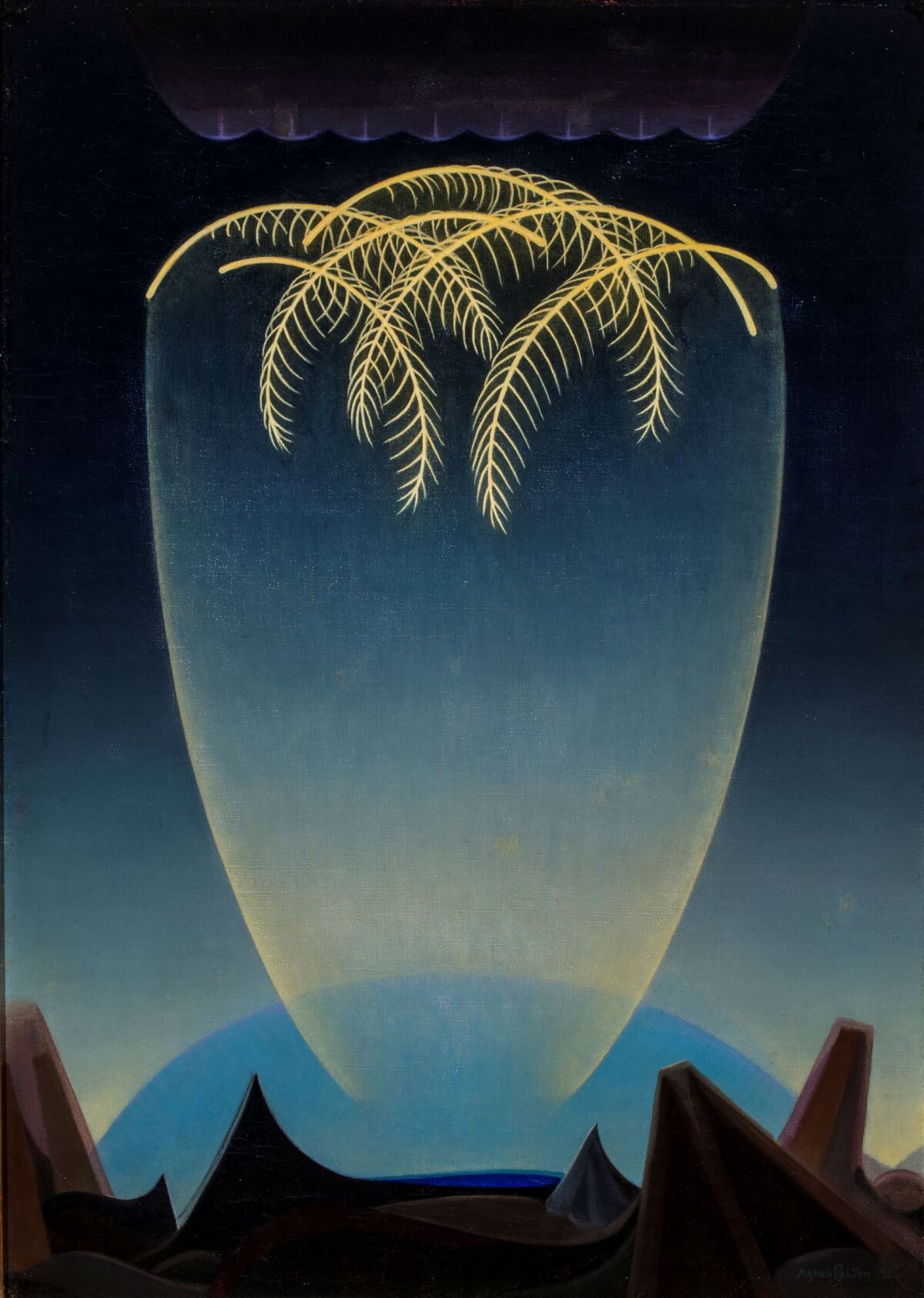

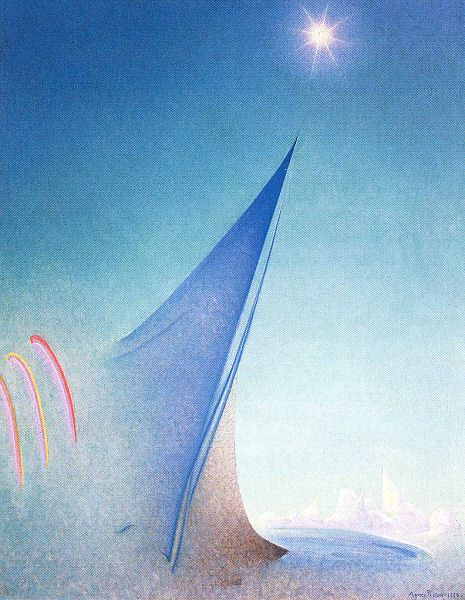

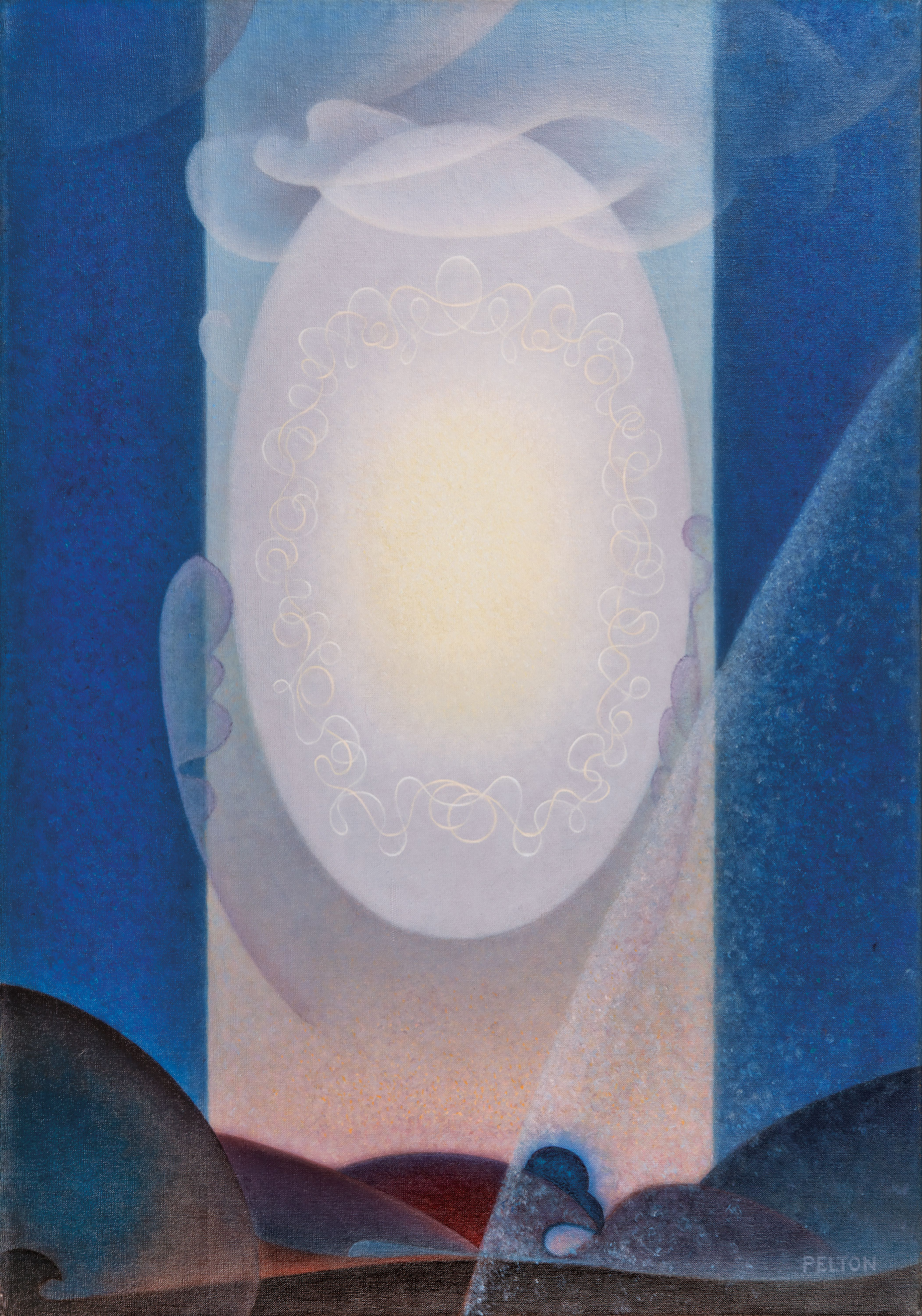

As a result, I’m trying to think of a new spiritual system that I can attach myself, and my transness, to. I think it’ll look a lot like the paintings of Agnes Pelton, and it will encompass everything I ever wanted and everything I will ever go on to do.

I’ll swim in the sea in Greece.

A shifting, a moving. Between worlds. A fierce intensity in the clearing as I find a relic in the dawn.

21/05/2023

Leave a comment