I am cold, and I want to remember a warmer time. After an unusually warm December, it seems the winter has finally caught up with us.

I’ve always seen myself as someone sitting in the cold, imagining countries in the sun. I am most definitely the ‘summer’ type.I think some of my most formative moments growing up were holidays abroad with my family. I like long evenings, the sound of crickets, warm pavements and the yellow forms of leaves under bright electric lights (walking back to the hotel).

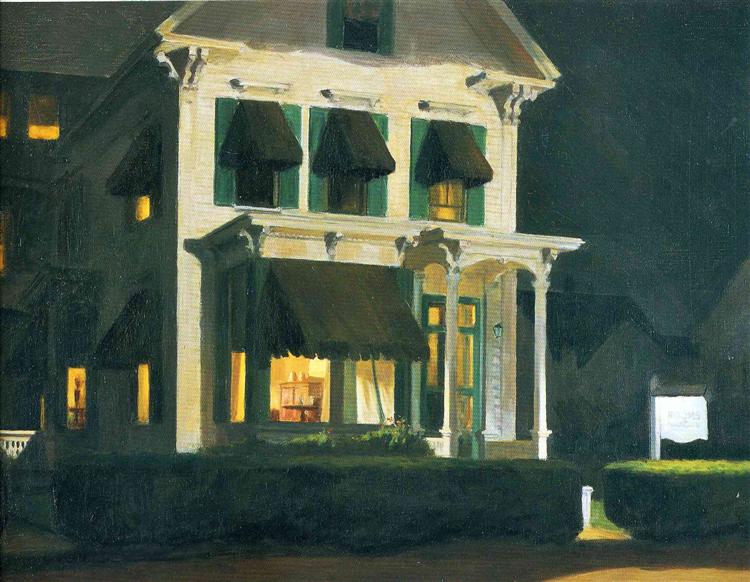

Much of my early engagement with art was as a form of escapism. In many ways, it took the place that my obsession with travel (invariably to warm places) had in my mid-teens.

I wanted sunny scenes- I wanted an artwork to transport me out of my body and into a warmer clime.

My interest in art for its meaning– that all came after the fact. The escapism came first.

I wanted to be a perpetual tourist, unknown to all, and with no anchors of place or community holding me back.

As a result, it’s not unsurprising that much of the art that I have produced- namely the long poem Sunset Sex with Bailey Jay, which mostly takes place in an imagined late summer in Richmond, Virginia, and the poetry collection Swimming Pool, Tennis Court, the opening poem of which occurs on a virtual, unreal plateau on some mountains outside Los Angeles, takes an unreal summer climate as the source of its aesthetic.

I wrote Swimming Pool, Tennis Court in an attempt to romanticise what I was then desperately trying to imagine as my future life as a gay man. By the end of the process of writing the collection, I had become unable to push my transness into the background- and the final poem, written in September 2021, represents an uneasy acceptance of the long road of transition I was about to embark on:

“A band of LED screens on the distant tower. London. Nighttime.

We let our hair grow long, and forget all we used to know.“

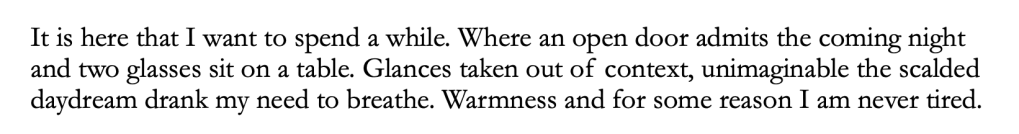

In contrast, the first long poem in the collection, titled ‘Swimming Pool’, was written in the height of my denial period. Much of the phrases included within it were written during the summer of 2020, as lockdown was beginning to lift, and I went most days to swim at a hotel in my hometown. I spent this period listening obsessively to music of the Canterbury scene, reading philosophy, and swimming. Like many of the unhappy periods of my life, I was desperate to not feel like my life was being ‘wasted’- so I pushed myself to achieve as much as possible, both in terms of learning new things and in becoming fit.

‘Swimming Pool’ takes place on a sunny hillside, half-rendered, and populated by my childhood memories and future fantasies.

From the start, I wanted this location to be a kind of simulation, wholly unreal, partly because at the time I was convinced that language itself, and by extension, poetry, was a simulation, and partly because I saw this collection as a test, a simulated version of my embodiment as a gay man, were I to go on living as one.

On this plateau, I was laying on a sunlounger, blinking in the light, trying to materialise my body without flinching – while, at the same time, I trying to get lost in the hills that surrounded the swimming pool. The male love interest in the poem- to whom much of the poem is addressed- was an idealised amalgamation of the all the men I had ever loved in my life.

I was split in two- both in love with the location, its promise of love and leisure, while at the same time anxious about the scene’s unreality, its inability to be truly rendered.

Less a physical location in itself, the plateau was an area of potentiality in which timelines of my future life could play themselves out.

At the time, I remember very consciously trying to incorporate lines that referred to my own body. Unlike the Bailey poem, I thought, I want to actually be in this one. Every time I did it, I resisted the urge to cut these references in edits- forcing myself, through discomfort, to embody myself: ‘I say my skin stretches as my chest rises’.

But, of course, the plateau was another escapism. It was an imagining of what my ideal life might be like to be ‘gay’, but not a man. Even in the section when I describe my sexuality, I transform it from the identity of gay maleness into the more vague concept of only ‘attracted to guys’.

The simulation was a failure- obviously. The lives that I imagined for myself from this plateau didn’t go anywhere, and within a year of the first notes I made for the poem in August 2020, I had accepted that I was going to have to transition to live how I wanted.

But, even now, having been living as a woman for well over a year, I’m still intoxicated by these summer landscapes.

They haven’t gone away, but their significance has certainly shifted. For example, in Reading 4, written in May of 2023, you can see them in the way I imagined a trans history in the Cyclades:

the sculpture seemed to present to me a new potentiality for my own corporeal existence as it gestated in my pre HRT brain. I saw a place opening up for myself. A thicket. A shaded space in the Cyclades thousands of years ago.

And, in that same post, when I discuss my feelings towards Molly and how I too wanted to be able to experience going swimming as a girl in the summer.

Now, I recognise that one of the most attractive aspects of my staccato living-as-a-girl-but-only-vicariously-in-bright-moments-of-potentiality was that in this hidden world of attribution and desire I was in no way limited by my male body. In fact, in this world, as in my dreams, I had no body at all.

The post ends with me envisioning what my trip to Greece would be like that summer- the first holiday during which I would be able to go out in a women’s swimming costume and go swimming in the sea:

I’ll swim in the sea in Greece.

The time when I wrote this blog was the time when I was really starting to feel happy, like my life was coming together. May 2023: I had a job, finally. Summer was coming, and I’d gotten through a very long, very cold winter. I’d taken a few pictures of myself where I really looked like myself. Since around that time, I’ve generally been very happy, but I will forever look back on that time, and that blog in particular, as being a bit of turning point- a peak in intensity.

It was also a time when I realised something really significant for those imaginary landscapes and experiences I’d been obsessed with- I could actually be in them now. I could be the girl swimming in the pool- a highly dysphoric and self conscious girl, yes, but a girl nonetheless. I didn’t have to be half-rendered any longer. And besides, summer was coming.

July 2023. Arriving in Greece, we spent several days in Acharavi- a quiet coastal town in northern Corfu- where my brother’s girlfriend Effie had grown up.

We stayed in her childhood home, which was a profoundly different experience to the usual cool white marble and stucco apartments frequented by tourists. It was all wood panelled, and had no air conditioning whatsoever. We would sit in the rooms and just sweat.

The house had several quirks- the showers barely worked, the bathroom door wouldn’t shut, and Effie’s room had been preserved exactly as it was when she left for England in the late ‘00s, complete with princess toys in pink plastic, fairy castles and dolls covering every surface. It was an unusual atmosphere, like the house had been vacated for an earthquake, and kept pristine just as it was.

We had arrived in Acharavi late in the day- almost 11pm- and had sat hungover at the ‘pool bar’ where Effie’s Greek father worked. He was very generous, and while I was nervous how he would react to me being trans, I was surprised when he, upon greeting us all for the first time, kissed me on the cheek twice. He shook my brother’s hand.

Maybe he was just an ally, or maybe, in the darkness by the illuminated pool, I’d passed.

He got us some delicious souvlaki and big glasses of cold beer. We drank them thirstily. With a heatwave set in and fires raging on the mainland, Acharavi was 30 degrees even this deep into the night.

I didn’t speak a great deal, but felt very happy to be there. I looked over the glimmering pool. The tourists who stayed in the small resort had long gone to bed. The pool was so inviting. It was a bright cube of blue in the warm darkness.

I felt like the big sister, and was proud of my brother, though I wished he’d stop talking so much.

Around midnight, Effie’s father drove us back to her childhood home and dropped us off. We went to bed, and I had Effie’s mother’s room all to myself. It was a very hot night, but I took a sleeping pill, and slept pretty soundly.

The next morning I got up slightly earlier than the rest of the group. Mum, Jack and Effie stayed in bed while I made coffee and got ready to go out to the beach- which was only around a 2 minute walk away.

By 10am in the morning, it was already 33 degrees outside. I got ready, slathered myself in suncream and walked down to the beach with my towel. On those days on the beach I read Harry Nicholas’s a trans man walks into a gay bar and Bellies, the latter of which I discussed at length in Reading 7.

I had certainly felt a little self conscious, going out in a swimsuit for the first time. But, to be honest, the beach wasn’t very busy, and no one seemed to bat an eyelid at me.

Jack, Effie and Mum arrived a little after me. The sea was cool and fresh, and very, very blue. I enjoyed looking out at the mountains of Albania on the horizon. They looked vaguely unreal.

A few days later, we were having lunch at the ‘pool bar’ again. I decided to leave early, go back to the beach, and have a swim on my own. Back in my teens, I had always wanted to go off on my own for a while during my family holidays.

When I was 15 I took great pleasure in walking into midtown Manhattan and around grand central station for an hour or two. And, in 2017, I had the most magical experience reading Walt Whitman in Ina Coolbrith park in San Francisco, overlooking the city.

So I arrived back at the beach, laid out my towel and took my blue shorts off, with just my one piece underneath. While by now this was not the first time I had gone swimming in a swimsuit, I hadn’t really had time to take it in and relax, as I had been talking my mum and Jack most of the time.

I wanted to do it again but alone, and just for me. I was happy with my swimsuit choice… I mean, it was just some cheapo two-tone blue slazenger one piece but the more glamorous types tend to be harder to tuck in from my experience.

As I approached the water, the pebbles and rocks became sharp and coarse. I trod over them tenderly, eager to become submerged as soon as possible so as not to get clocked.

I felt intensely self conscious, stood in the open like that. But I got to the water pretty quickly, and by the time it had become a metre deep, was already buoyant in the shallow water.

All that morning, I had had a headache, and was tired and drowsy from the sleeping pill I took the night before. But, as I swam further out, my head cleared.

While I certainly wasn’t the only person on the beach, it was quiet enough that I really felt like I was out on my own.

I floated, feeling the water’s buoyancy, my whole body enveloped in blue. I could hear little save the clear sounds of the waves. I felt a calm all over me.

It was as if everything had stopped, like I wasn’t rushing, and didn’t need to do anything. There was nothing in my immediate future to worry about. It was just me, swimming in the blue.

I thought about the colour blue, and how I had always saw pale blue as the colour of my own liberation- as well as my femininity. I thought about the way the hills almost vanished on the horizon.

I paid close attention to the feeling of the water around me, grounding myself in its coolness, feeling the safety of the straps over my shoulders, as if the blue swimsuit itself was buoying me up in the bright water. I breathed very deeply, almost meditating.

It was all so intensely beautiful- the landscape around me, further out to sea, and back to the grey-white pebbles of the shore. Briefly, the image of the poolside plateau, and those imagined holidays with future boyfriends from ‘Swimming Pool’ flashed through my mind.

They had no urgency- I just felt them wash over me- and remembered a section from the poem about the colour blue, and how it still rang true, even if so much in my life had changed since then:

I breathed, and waded out, and thought, I’d so love to make out with a guy right now.

Even now, writing about this, I feel a profound calm wash over me- one that I almost never feel in my everyday life. It is this calm that I see as the source of the spirituality that I used to feel and aim to feel again. It’s a feeling of acceptance, an unconditional love.

There I was: floating, swimming, feeling alive and present. A girl. Nothing I have to do. Nothing I need to do to achieve it. No one I need to tell.

It had been a very difficult few years- coming out to people, the horror of arranging doctors appointments, the unbelievable amount of admin, deed polls, letters and applications. Now it felt like all that was behind me.

I thought of a line I’d read in Harry Nicholas’s book on the beach prior: something about transition as an act of self love- for many, myself included, the first act of self love we afford ourselves. The first time that you allow yourself to be that one thing you want to be but that you rejected with all your power, hating yourself and how you were perceived, the options available to you.

I felt corporally present, perhaps in a way I haven’t since childhood.

There’s a section in Nicholas’s a trans man walks into a gay bar, where he talks about the first time he went swimming as a man. Titled ‘The Ponds’, Nicholas describes the elation and freedom he felt going to Highgate men’s pond in Hampstead Heath after top surgery, baring his chest just as the other men did:

I could feel the sun’s heat on my shoulders and I cherished how good it felt. To not have any swimming costume imprisoning my shoulders or sweaty fabric cupping my breasts. I noticed, too, how my chest hair moved to the rhythm of the water. (136)

He describes it as a kind of homecoming: dysphoria had previously forced him to steer clear of water based activities, especially in his early transition. Now, he was able to enjoy the water as he had as a child:

We giggled. This was good. This was freedom. This was the happiness I’d worked so hard for. (136)

Nicholas talks of this experience as a reclamation of an innocence and an agency that cisnormative society had taken from him. While by no means free of dysphoria and self-consciousness, his swimming emboldens him:

I left the pond through the gates, feeling taller and fuller than I did when I entered. (137)

After I’d spent a half hour or so in the water, I swam back to the shore, towelled off and headed back to the house to siesta.

I squeaked back in my pink sliders, sat down in the bath – the shower hoses had to be used by hand as they were not attached to the wall- and washed the sand off my body. I sprayed the cool water over myself in a way I would never have paid attention to my body when I was a ‘boy’. When I was a boy I flinched at the sight of it, and put on a stoic face not to bolster my sense of masculinity, but to hide my discomfort.

Once rinsed, I changed into my shorts and T-shirt, went downstairs and into the fierce heat of the balcony. I laid my swimsuit over the railing to dry in the sun. It dripped onto the hot tiles.

This had felt like another turning point- while I was still very dysphoric, and only felt good about myself in short blasts, I had proved to myself that I could do it. Even though I didn’t fully pass, I could do what I wanted, and live as a woman, and just needed to have confidence in myself, as difficult as that feeling was to come by.

At the same time, it was in Greece that I started to make the decision to stop using the men’s toilets and start using the women’s full time.

While I didn’t actually make this shift until a month or two later, there were several occasions in Greece and shortly after that pushed me to accept that it would make more sense, and be safer, for me to use the women’s.

I had put off making the change because I really, really, did not want to get harassed in the women’s toilet or asked to leave. I knew that would be too big of a blow. So, for many months, I stuck it out going to the men’s even when, on many occasions, I was actively harassed or told to leave because they assumed I’d walked into the wrong toilet.

During this time, there were more and more situations in which I was, to my surprise, passing:

- Gatwick airport 14:32pm: men’s toilets, a cleaner makes eye-contact with me and limply points towards the women’s. I say thank you, and I don’t know if he is already reconsidering that decision.

- Arriving at the pool bar, Effie’s father, Andreas, gives me a two kiss greeting along with my mother but shakes my brother’s hand. Three days later, on the day we leave, he shakes my hand before I leave as if to correct his mistake.

- Historic district, Athens: walking through the touristy streets a man says ‘hey ladies’ to my mother and I to attract us into a restaurant.

- Athens airport, on the way home- a woman stops me to warn me ‘that’s the mens!’ before I walk into the toilets. I say ‘that’s fine’, and continue anyway to avoid the embarrassment of getting clocked.

Then, when I was home in London, I go to the men’s toilets in the Elephant & Castle Wetherspoons, where a group of drunk men shout at me to get out, exclaiming ‘this is the men’s! this is the mens! get out!’

It was only after this experience, and others like it, that I switched to the women’s full time.

I often think of this blog as my first successful attempt to write about winter, and not see it as a waiting period- an intermission between two blocks of more important, and more substantial, vivacity.

It was my winter in Walworth where I started to feel as if winters were worth living, even if I was working long hours in retail for much of it.

But I still look forward to the summer more than anything else. Future summers, real and imagined. And more to come.

I want to end with the last stanza from ‘Swimming Pool’, which I think still holds true for me, though in a different light.

21/01/24

Leave a comment