“The Goddess” to me means the historical female deities from different cultures. But it also means the divine being, or spiritual power, as it comes into existence in ourselves and in the universe around us. (p.27)

I finally got round to reading Rachel Pollack’s 1997 book, The Body of the Goddess, which I’d started not long before I moved back to Camberwell, but gradually put down during the excitement of the move. I’d been wanting to read this book for a while: it so obviously ticks so many boxes for me.

Rachel Pollack, who I have mentioned before in reading 9 was a trans woman who grew up back in the 1950s in America. She transitioned in the second half of the twentieth century, though I’ve been able to find very little information on this and the facts of her transition. What we do know, though is that during this time she wrote in several fields, all slightly obscure or off-piste in their own way.

For one, she wrote science fiction and fantasy novels, one of which, Unquenchable Fire, won the Arthur C. Clarke award in 1989, while another, Godmother Night won the World Fantasy Award, and was nominated for a then relatively new Lambda Literary Award for transgender fiction. Both of these books developed an esoteric mythology centred around women and the natural world.

Around a similar time, she wrote for DC comics, specifically the series, Doom Patrol, and is credited for adding discussion of menstruation, sexual identity, and transsexuality to the world of comic book heroes (I wonder what the fan base thought of that!).

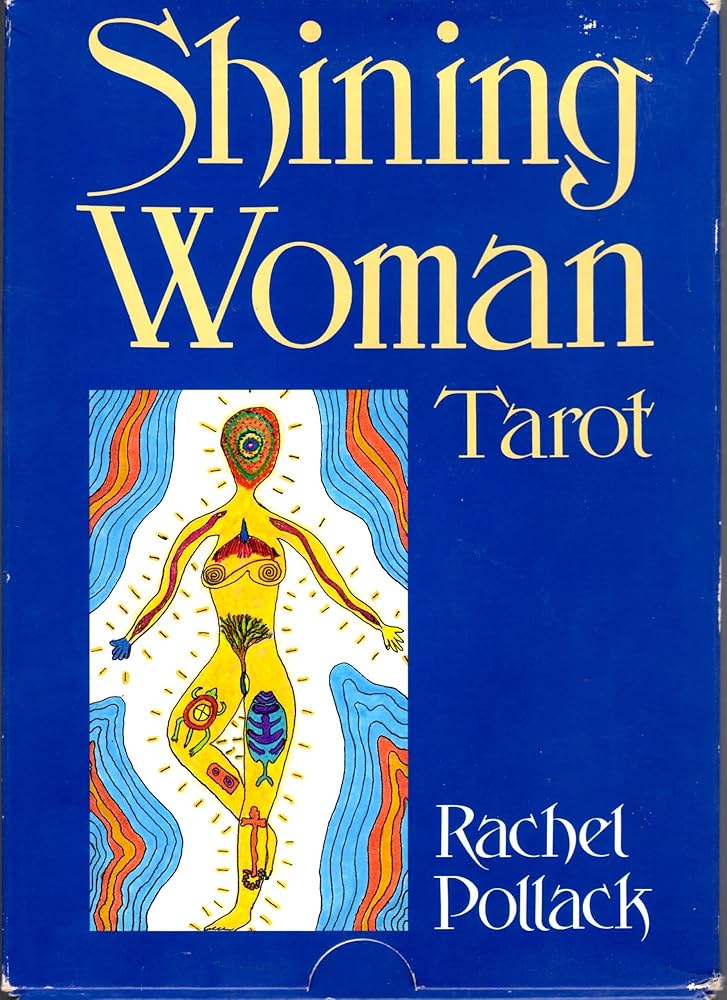

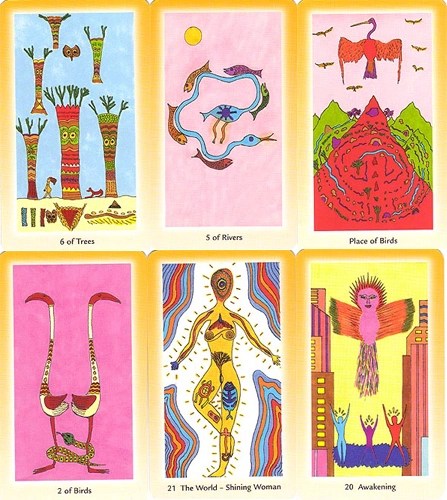

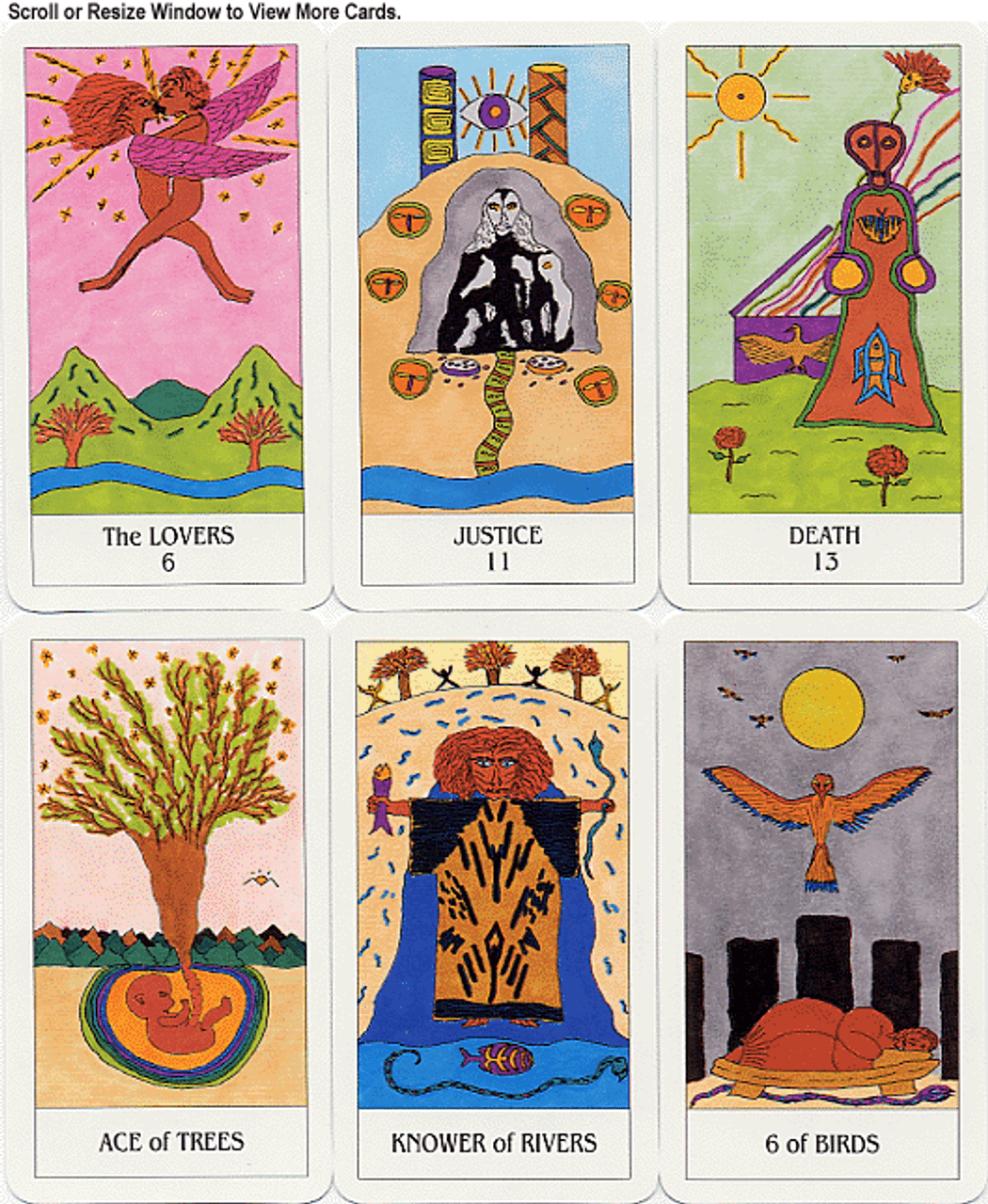

She also gained a cult fame for her influential work in the tarot field, writing 78 Degrees of Wisdom, which, according to wikipedia, is regularly cited in the community (who knows!). Around this time, she also created her own tarot deck, Shining Woman Tarot, which was later renamed Shining Tribe Tarot.

I know nothing about tarot, but I can certainly appreciate the beauty of some the designs she came up with.

Then, later in her career, she published a sole non-fiction book: The Body of the Goddess, with the subtitle, Sacred Wisdom in Myth, Landscape and Culture.

The through-line between all of these otherwise quite disparate and usual creations is Pollack’s abiding interest in spirituality, the natural world, and the body- especially the female body. She also wrote, quite consistently, about the trans experience- though, interestingly, she often declines to mention her own trans identity.

This omission was, almost certainly, a byproduct of the culture of fear that surrounded those who transitioned during the late twentieth century. To even be considered for medical treatment, transsexuals had to pass perfectly, meet rigorous diagnostic criteria- which generally involved researching the right things to say before hand- and then promptly reintegrate back into cishet society without making too much of a fuss.

Reading The Body of the Goddess, without knowing about its author, for example, one wouldn’t know that Rachel Pollack was trans. But her omission probably makes even more sense with this book in particular- one which, if anything, slots into the canon of ecofeminism, if not feminist spirituality. Knowing that much of her audience may have been indoctrinated into transphobia by racist cringe lords like Mary Daly, author of Gyn/Ecology – she probably thought it best to leave out her minority status, and instead don the unmarked objectivity assumed by authors like Daly.

But the result of this is that Pollack is actually seldom discussed in the trans community. As an example, upon discovering her writing myself, I was shocked that Bailey, my spiritual guide and trans godmother during my late teens, had never mentioned her to me. She’d spoken at great length about her fascination with the occult, spirituality, tarot and transness, but never mentioned the author who had brought all of these together.

Another reason for Pollack’s relative obscurity, I think, is the unfashionability of spiritual ecofeminist writing. Many now look back on the ‘70s era of Daly and her ilk (she was dissertation supervisor for Janice Raymond’s The Transsexual Empire- the key text of anti trans psuedofeminism) as being inherently colonial, racist, essentialising, and, most of all, cringe. In the trans community, I think many would see it, and it’s return to nature, as marred by transphobia and privilege.

This isn’t helped by the fact that trans culture, specifically trans female culture, has taken on a seemingly contradictory aesthetic that upholds the supremacy of technology – more along the lines of Donna Harraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, and Helen Hester’s later Xenofeminism. On a cultural level, a lot of this aesthetic comes from music, taking its harsh, electronic, and glitchy feel from artists like 100 gecs, Sophie- and Wendy Carlos, a contemporary of Pollack’s, whose 1968 album Switched-On Bach was instrumental (pun not intended) in bringing synthesisers into popular music.

[As an aside, it’s weird how trans women’s music in the cultural imagination is so much more specific and limited than that of other LGBT music. What does bisexual music sound like? What about lesbian music? It’s hard to come up with one thing or aesthetic. I mean, we can identify most ‘gay’ music because it sounds like boring trash- but beyond that, it’s more of a mystery. Trans women’s music’s association with brash electronic and glitchy soundscapes is a weird, and contrived, cultural phenomenon- why does everyone think of this and not, for example, Ethel Cain, or Laura Jane Grace? I don’t know!]

Don’t get me wrong- I’m generally very inclined towards the brash technological vibe that much contemporary trans aesthetics revel in. But I think its cultural enormity has, sadly, led to a general ignorance towards the work and spirituality of people like Pollack. People still mention how trans women used to be spiritual and religious figures in the distant past, but they seldom go much beyond that.

I don’t think that these two sides of trans female culture need necessary remain separate. Like, nature already is technological. That’s that fuzzy, electric sound underneath everything. If we met angels they would look like a giant mass of wires.

Alongside The Body of the Goddess, I’ve been really getting back into the kinds of spiritual writing I used to love when I was around 18-19 years old.

I’ve probably explained this to some degree before on here but it’s worth repeating that I tend to see the spiritual awareness I had in my late teen years as always something I’m working towards regaining. I see that time as one in which I saw things very clearly, and was very satisfied with life as a result. There was always this sense, as discussed in reading 7, that I was moving towards a great revelation, that there was some secret under everything. I guess that now that I’ve discovered my own personal secret I need to work towards the other much larger secret that underlies everything (what is that humming sound!!).

In short: I stopped believing a lot of the spiritual stuff I used to believe because I realised I was trans. And the crisis of that took the warmth and the lovingness from my imaginations of what the universe was really like. I’d figured out a secret, and I had to throw it away- the awe, the mystery- along with everything else.

Now that I’m pretty stable and secure in my life, I’ve made it my goal to regain my old spiritual convictions. Even though it went into hiding, it’s not like I ever lost that capacity. I remember reading someone describe the capacity for spiritual and religiosity as an ability to experience a kind of ‘oceanic feeling’– the feeling of something infinitely vast and loving that is beyond us. And I certainly have that.

Anyway, I’ve been reading the devīmāhātmyam, which is a Hindu text dedicated to the Goddess- and the idea of the underlying nature of reality as female. I’ve already found it very moving and exciting- especially seeing how obsessed I used to be with the more famous Hindu texts like the Bhagavad Gita and The Upanishads – the latter of which I got Bailey to read at the time (- and she still mentions it to this day!)

I don’t think I’m ever reading these texts to find a comprehensive philosophy by which to live my life. As with my description of John Ashbery’s writing in reading 16, when I’m reading something in this way, I’m more looking for fragments and ideas that I can repurpose into my own, ideas about the world that are based on my own intuition.

That’s what I’ve been building in my head since I was a teenager really- an esoteric and idiosyncratic spirituality built upon my intuition. A lot of it took a great deal of influence from stuff I read at the time, Hinduism, Heraclitus, the Tao te Ching, Plato, Huxley and his reading of Blake… but, in the end, it’s always distorted, or simplified in my conception of it. I pick the bits I like. Or the sections that feel intuitively true or real to me.

Most of these ideas went into the long poem I worked on during the end of my teen years, Sunset Sex with Bailey Jay, which is by far the most comprehensive description of my own personal spirituality that I’ve ever made. Now, I see it as a poem that is about the Goddess, and my biggest dedication to that way of thinking.

Though I hadn’t read it yet, the poem has much in common with Pollack’s The Body of the Goddess, – its interest in the natural world and its cyclical patterns, and my depiction of Bailey, who is regularly described as a ‘prophet’ and ‘goddess’.

Pollack outlines a spirituality based upon the female body that, she argues, predates patriarchal religions and social structures. She finds evidence for this in the proliferation of female fertility symbols, female mythologies, cave paintings and land structures, all of which uphold the female body as a powerful, life-giving force linked with an inherent spirituality. (See reading 4 for my reading of a Cycladic fertility sculpture).

Her book is about the body of the Goddess because the Goddess is always already embodied. Unlike the male deities of patriarchal religions, She is not an abstraction but a divine reality in which we already live and coexist. Pollack’s idea of the Goddess’ body rejects the ‘purity’ of male god abstractions and embraces the realities of the body: sex, sexuality, birth, and death.

She describes what she calls ‘a religion of basic realities’:

The body remains our fundamental truth. I do not mean by this only the human body. The African Goddess Ora expresses Herself as lightning, and as rivers. The prehistoric Goddesses of Europe and the Middle East took the forms of fish, or bees, or trees, or toads, or vultures. To us today these images seem strange, even childish. We are used to thinking of God as an abstraction. But these images are not arbitrary, let alone trivial. They came from a deep and specific knowledge of animals and plants and the processes of life. That knowledge joined with a spiritual awareness, a sense that divine reality moved in people’s lives at all moments. How natural, how real, to bring together the understanding of physical existence and the intuition that spirituality flowed through all experience. (p12)

This way of thinking makes total sense to me and feels true on a fundamental level. I think this is because a key characteristic of the way I think and the way I want my spiritual system to work is by metonymy. I say this because I think that my spiritual convictions feel most affirmed and real in example and physicality. For instance: looking at something that jumps out as instinctively beautiful and meaningful- sunlight cast on the side of a block of flats, or a fierce green on a tree’s leaves- to me, these things intuitively mean that the goddess is real and that the underlying reality is loving and there for us. But I don’t believe that there any real hierarchy between the thing and that to which it refers- the light on the block of flats isn’t merely a sign of it- it is it. That’s what I mean by it being metonymic. Those small instances are the underlying nature of reality- the oceanic feeling- the humming in the wires … they do not merely refer to it as some separate abstract thing. There is no thing that is separate. The Goddess is always immanent.

I was thinking something like this back when I wrote the following in the Bailey poem:

Deep-field on a tiny stretch of sky:

Planets and planets all on the same plane

Like a painting, where it all happens at the same time- there is

Nothing outstanding. Nothing we don’t know.

At the time of writing the Bailey poem I came to see the moon as the most precious and spiritual thing:

If I breathe out too much I wheeze

And go into a coughing fit:

The sky pale purple, strained like an iris,

Above us, the moon huge and short-sighted.

What is the female presence that delights,

Has always been there? Stomach ache.

Fear of dying.

Of course, Pollack writes of the significance of the moon as a female symbol at length. In this case, the moon, I think, was quite straightforwardly, Bailey-as-Goddess – she who comes out at night (we mostly talked at night on account of the time difference)- but it was also my transness, short-sighted, blind to itself, though huge and always in the background.

In chapter 7, ‘The Body in Song’, Pollack describes gender-changing rituals, especially among Cybele’s (the great mother goddess) Phrygian worshippers, writing:

The fullest expression of genital sacrifice comes with the gallae, who followed Cybele from Phrygia to Rome (…) The gallae made their offering as part of the long rites of Cybele and Attis on 24 March, the “Day of Blood.” (…) After their self-emasculation the gallae ceremoniously received female clothes (…) and were described as wearing bridal dresses for their initiation into the service of their Goddess. (p.184)

Occurring at the time of the Roman festival of spring and mirroring the movements of the planets in the Spring Equinox, the Day of Blood celebrated the rebirth of spring. With the blood reflecting the beginning menstruation along with the start of spring, the practice has much with common with many pagan celebrations of the Spring. Pollack writes elsewhere:

The name “Easter” derives from Eostre, a German Goddess of spring, who’s name in turn is connected to “estrus”, female fertility. (p.20)

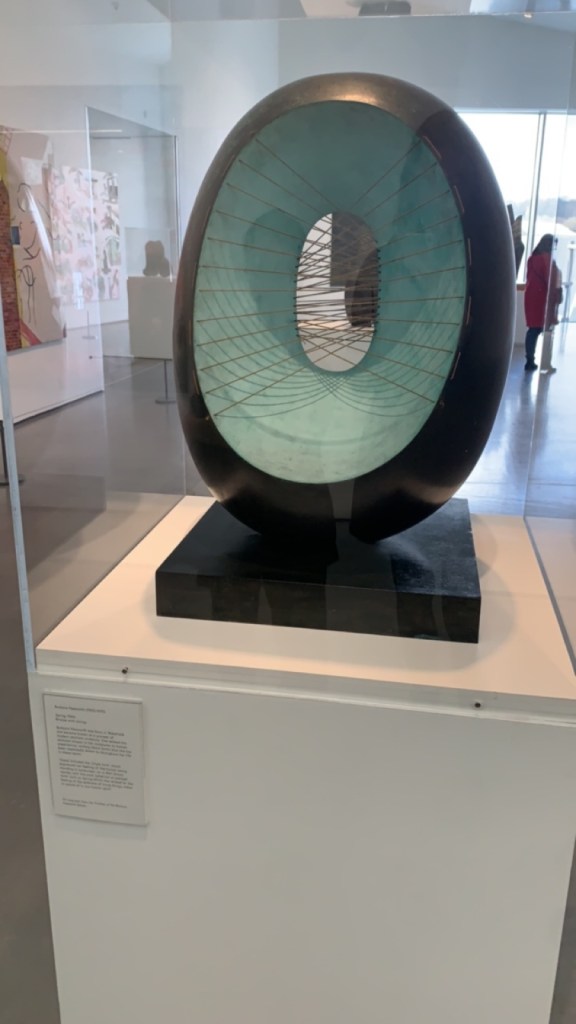

This etymology carries through, of course, to the hormone ‘estrogen’. In February this year I remember standing in The Hepworth gallery in Wakefield, a pilgrimage undertaken by myself and Molly, and looking at Barbara Hepworth’s sculpture titled Spring.

We both agreed it was our favourite sculpture we saw that day- especially, I think, because we ourselves were just coming out of a long winter into the spring. There was something thrilling about the colours Hepworth chose. The idea of spring as a blue door.

Hepworth’s sculpting of holes through solid forms and strings cast through them seem to say something intrinsically real about life and reality- one much like the images Pollack describes. The idea of passing through something, without knowing it. And the strings as a journey through.

Pollack makes the comparison between the gallae and trans people clear, though she never names herself as one of them:

The gallae resemble contemporary ‘transsexuals’, a word that means ‘cross-sexed.’ Touched by a strong sense of belonging to their opposite sex, transsexual people seek out surgery and other means to change their bodies. The body thus becomes an expression, or a medium for a deep and passionate desire. (p. 186)

The practices of the Gallae spread as far as Athens, Northern England and London, where ritual equipment from the era has been found in the Thames.

Pollack writes a lot about death in the book. Just as Persephone must, for half of the year, return to the underworld, so is there a darkness etched into the patterns of life.

The darkness is the underside of the spring, but also what makes it real and gives it its vivacity. In her descriptions of prehistoric fertility rituals and inhabitations, Pollack describes how the caves in which people lived could have been seen as parts of the divine female body. In this way, caves, especially those with religious significance, had a metonymic connection to the inside of the female body- and were viewed as place of new life as well as darkness, unknowability and, also, death.

Reading Pollack’s descriptions made me come to see death as an enfolding back into a bright darkness. This is the same darkness that we see in the night sky, and is that which brought us here only out of love for us. The Goddess gave us life to see what ours, in all its specificity, might be like: the central fact of our existence being that each person, each thing, is entirely different. Each of us will live out our experience, and, so doing, cast a thin line across the sky.

The people we come to know, spend time with and form connections with cast their own lines, too, and where theirs intersect with ours is very precious and immaculate.

I do not mean to say that in living out our lives we cast a definite line that is a physical entity in itself but more that I believe that our lives, on an individual level, are a way of reading that night sky. Each life is like a constellation- not an actuality in itself, but an interpretation of a larger phenomena that can and must intersect with other constellations.

In keeping with this, I believe that our goal in life should be to collect experience according to our desires. To follow our own desires to their natural endpoints means to discover what they, and in so doing, what we, are. That is appreciation of the code in its purest sense- appreciating what is already fixed and preset- and following it to its endpoint. No one knows what they want at the start, but the process is in discovering what she gave us and where it will lead. The end is already in the beginning, and all that. Our memories then collect, like abstractions clinging to the edge of trees. So doing, we cast a bright line… but most important is the way it slots in with other lines, the way it shares its stars with others. That’s what holds them all up there together.

The night sky is a very natural metaphor, but I think it is no different to an immense piece of technology. (Do I mean metaphor here? I don’t mean to say the night sky refers to something else, I believe that the lines are cast very literally in the actual night sky…)

Bailey comes back metonymically as natural forms throughout Sunset Sex with Bailey Jay:

The context was bullshit. Not knowing.

It’s the mystery that matters, the not so distant

Abstractions clinging at the edge of the trees; the darkness,

And the fragrant air.

But, in the poem, she was just as much a force of technology as she was of the natural world. After all, the interface through which I interacted with and knew her was Snapchat messages and the pictures we sent back and forth. At the same time as she was the moon, she was a collection of digital artefacts sent through the night sky, a series of messages- an ongoing pattern, night after night. She only arrives, in the first stanza, after the ‘viewfinder’ has waited for her – she was just as much a mass of wires as she was the wind in the trees:

Telegraph wires, wires converging in violet night,

Strung over the sky-scape, swaying and jittery like nicotine

And, in the poem’s final image, Bailey, the Goddess, embodies the intersection between the natural and the technological: a real life Goddess as a mass of aeroplane trails in the bright blue sky:

Just walking, towards the place

Where I’ll find you,

And before I can cross the road you’re already talking.

I turn, disorientated. They make no sound overhead.

The sky is crosshatched with white lines.

Almost right from when I began writing it, and throughout the 2 years during which I worked on it, I knew that this image would conclude the poem. There has always been something liberating and thrilling about seeing a plane in the sky, casting a thin white line in the blue. Growing up, especially, the sight of a plane meant a kind of escape- to other lands and other lives.

When I wrote it, I saw the sky as one crosshatched with all of the lives we could have and still could live. One of which, I think, was the life in which I was a girl- or one in which I became a girl. Up there, in some unknowable language, they told the story of everything as it happened and stored it all there for eternity. One thing that I knew was up there, if I could read such a thing, was whatever connected my life and Bailey’s. It was the time we spent together, yes, but it was also something else. A pattern, an affinity.

I saw the network of lines, intersecting in the bright sky, as one giant mass of potentiality: a great big mess of wires humming- each part of which was a kind of magical and preordained thing.

It was a miracle they were even up there. So great and so big in the sky.

15/09/24

Leave a comment