The nights are colder now, I’ve been finding myself very tired in the late evenings, and often go straight to sleep without even reading before bed.

For one of the first times in my life, it’s actually been pleasant, feeling the nights draw in, and the air get colder. And it’s been a great month- I feel like I’ve really turned a corner, or at least gotten back into enjoying my life in a simple way that I hadn’t really been able to since around April of this year.

I’ve decided to start printing my photographs, so that I have physical copies. I’ve realised that I can’t really, truly, trust iCloud to hold what is the sum of my most prized possessions. So, I’ve ordered some prints- just the highlights. And I’ve bought a photo album to keep them in.

As you can probably imagine, photo albums are harder to come by these days- or at least, it’s harder to get a nice one. Most of the ones on offer, for example, tend to have a tasteless section of writing on their front covers, saying ‘memories’, in a calligraphic font, or ‘together always’- that kind of trash.

It sounds old fashioned, ‘photo album’. Whenever I think of it, a section from John Ashbery’s long poem, ‘The Skaters’ comes to mind. ‘The Skaters’, is, in my opinion, the first poem where Ashbery came into his own and solidified his style. Published in his 1966 collection, Rivers and Mountains, the poem, almost 10 years before he was met with the critical success that followed him for the rest of his career, contains some of his best, and most affecting stanzas. Like this one, from part one:

We children are ashamed of our bodies

But we laugh and, demanded, talk of sex again

And all is well. The waves of morning harshness

Float away like coal-gas into the sky.

But how much survives? How much of any one of us survives?

The articles we’d collect— stamps of the colonies

With greasy cancellation marks, mauve, magenta and chocolate,

Or funny-looking dogs we’d see in the street, or bright remarks.

One collects bullets. An Indianapolis, Indiana man collects slingshots from all epochs, and so on.

I return to that passage every so often, and frequently get teary-eyed at the ‘But how much survives’ line. I think it’s the image of the previous line that sets it up so perfectly. The sense of hard times passed and vanished.

That’s what I’m trying to do in making an album, I guess, collect- to make something that survives, at least survives iCloud going down, survives for me.

There’s always an interest, in Ashbery’s writing, in the idea of information being lost, and the impossibility of fashioning anything that truly can stand the test of time. All of his stanzas are a kind of collection, now that I think about it- a bringing together of disparate objects- like an over-stacked mantelpiece. Like Elliot’s ‘fragments’ ‘shored up against’ his ‘ruins’ in The Waste Land, but with a joy in the collecting as an act of creation, and a humanist belief in the reader’s capacity to transform and create anew.

Photo albums are a little different though. They, at least usually, have more of a sense of chronology to them. They, at least more obviously, tell a story. But they have that same sense of futility, and, in a similar way, distort the truth, make new histories, in just the way that a collection of slingshots might.

I mean this in the sense that, flicking through an album, we rewrite the history each time in our heads. And, the more distant those memories become, distort, and simplify their shape until, at least for me, they become so abstract as to just become the photograph itself, surrounded by a blur of softening associations in the background. That day was a blue dress and yellowish light on my face, for example. And I think it was warm that day.

And we romanticise it too- the trivial annoyances that plagued us, and were perhaps at the forefront of our minds in the moment, get forgotten, until we only remember the pretty lighting, the sense of freedom over the water, or the having fun with friends.

And, in the grand sweep of those readings, flicking through an album with photos from our life, things feel solid, meaningful, and fated in a way they so rarely do as they’re happening. The big narratives come out, and the crap, the morning harshness, gets sounded out.

Weirdly, I’ve come to begin romanticising last Autumn and Winter in my life- the time when I was living in Clapham South, in a grotty little room, with a load of strangers. Settling in had been difficult there, but, looking back, it was actually a very happy time in my life. I think of the time period in which I wrote Readings 8-12 as being a really positive few months for me. I was isolated, in some ways, yes, but I was also independent and stable in a way I don’t think I ever had been. It had felt like my first winter lived as myself, in a stable job, with great friends- and little to worry about anymore.

The material aspects of my life, since moving back to Peckham, have been greatly improved since then. But it shouldn’t come as a surprise to readers of this blog that the spring and early summer of this year was a really difficult one for me. I felt very terrible, and very hopeless, and like all my progress over the last few years had come to a dead end, a waste.

I have photos from that time- but, looking at them now, they show nothing of the hardship and anguish I went through. They show pretty little scenes, and, the more time passes, the more I forget how bad things got.

And it’s crazy, too, how fast things can change. The past few months- since the late July until now, have been brilliant. I’ve been really happy. Photos in the album.

‘The Skaters’ was one of the first things I ever read by Ashbery. It was sometime in 2018, and I was reading a big anthology I’d bought on Abebooks, Postmodern American Poetry, edited by Paul Hoover. This collection was, by far, one of the biggest influences on my tastes in poetry over the following years. It is a vast, and amazing, assortment of radical poetics from Charles Olson through the Beats, Black Mountain poets and New York School up until the twenty first century.

I remember reading ‘The Skaters’ and just being electrified by it. I’d never read anything like it before. I was struck by its abstraction- it had felt like something I had been waiting for for a very long. To me, someone who had mainly been preoccupied with Modernists like Pound and Elliot, and the later Beat and Confessional generation – it seemed to just totally fit, and totally make sense. I knew straight away that Ashbery was going to be very, very big for me. And I was going to be off to Uni soon, and would finally have the chance to study all of this stuff.

I loved how the title, ‘The Skaters’, brought forth this image of a hypnotic kind of movement, a wild assortment of different movements and velocities and directions. A kind of meaning pulled out of disorder.

The anthology included just part one of ‘The Skaters’. At the very end of that part, Ashbery mentions a photo album, and it’s this line that keeps flashing into my mind.

Inventing systems.

We are a part of some system, thinks he, just as the sun is part of

The solar system. Trees brake his approach. And he seems to be wearing but

Half a coat, viewed from one side. A “half-man” look inspiring the disgust of honest folk

Returning from chores, the milk frozen, the pump heaped high with a chapeau of snow,

The “No Skating” sign as well. But it is here that he is best,

Face to face with the unsmiling alternatives of his nerve-wracking existence.

Placed squarely in front of his dilemma, on all fours before the lamentable spectacle of the unknown.

Yet knowing where men are coming from. It is this, to hold the candle up to the album.

On the topic of ‘The Skaters’, and the image of skaters, a few weeks ago I went to an exhibition with Molly and her sister Abi at the Tate Modern. While ostensibly about Expressionism, Kandinsky and the Blauer Reiter, it was the paintings by Marianne von Werefkin that totally stole the show, and absorbed most of our attention as we moved our way through the busy gallery.

One in particular, was called The Skaters, and depicted a group of slender, shadowy figures skating in a rink at night.

It has a peculiarly disquieting feel to it- a sense of being haunted- even though, on the surface, it’s a picture of people having fun. I love the warm orange glow of the buildings in the extreme right of the picture, and its contract with the cold blue tones of the rest of the painting- and the strong sense of inside and outside that becomes apparent the more that autumn, and later winter, takes hold.

The moon, too, overlooking it all, gives a kind of spiritual, or even cult-like feel to the people’s act of leisure. Is this, instead of a scene of carefree fun, an image of a religious ritual- a hypnotic and cyclical moving around an invisible central point? Do the people even know that they are taking part in it? Or are they doing the moon’s work while being unawares?

I think for Ashbery, too, part of the interest in the image of the skaters comes from the way that they take on a totally different meaning from a macrocosmic scale. While each person is having their own journey around the rink, from afar they are all a part of one phenomena, a circuit of skaters operating to one mysterious, and yet utterly convincing, pattern.

And that’s what I’m saying the process of making, or reading, a photo album is. Taking a macro view- applying a sense of order and narrative direction, to what is oftentimes, in the moment, a disordered and confusing fragment of a larger spectacle.

It is this, to hold the candle up to the album.

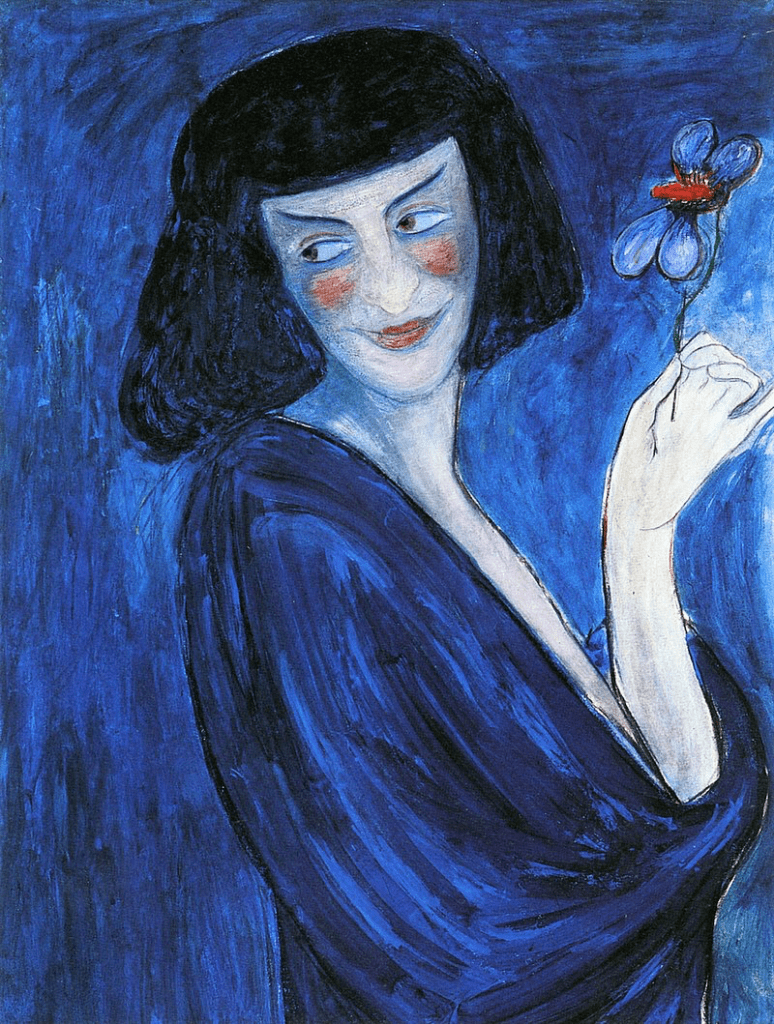

My favourite painting in the exhibition, though, was another by Marianne von Werefkin, titled The Dancer. The painting depicts a friend of Werefkin, and someone she was said to be fascinated by: Alexander Sakharoff.

Sakharoff was a Russian dancer and teacher known to dress in androgynous and women’s clothing. In an age of widening discussion of women’s suffrage and rights, what most interested Werefkin was Sakharoff’s sexual and expressive freedom and eschewal of societal conventions.

I love this painting. It’s easily one of my favourite portraits of all time. And I know I’m easily won over by a black bob, but it’s more than that. It’s just so expressive, and stylish, and beautiful- and, even thought Sakharoff never came out as trans, and died in the ‘60s, I want to believe that she was. I mean, how else would being trans manifest in the early 1900’s? This was before Hirschfeld, even.

I bought a print of The Dancer that day, and just got a new white frame for it from New Cross after work yesterday. I’m going to put it up in my room today.

This is just going to be a short post today- I had no plans for this one, and have literally just made this all up as I went along. But I’m glad to be posting more regularly again, and glad to be able to be enjoying my life again. These last few months, it’s been so lovely, and more and more that difficult spring feels like a blip, a wider consequence of cruelty inflicted upon me by another I held dear, more than anything else. Months later, I feel good about things.

After the exhibition, we got lunch at one of the Columbian bakeries at Elephant, before heading back to my place and to get dressed to go see Chappell Roan perform live in Brixton. I felt really lucky to be able to go and see her, especially so close to home.

I didn’t have anything pink so I went with a purple-blue dress with big sequins, as well as some rhinestoned fishnet tights I got especially for the occasion. We drank cans of lager in the queue, and it was fun to be so dressed up and glittery in the middle of Brixton on an early saturday evening.

The highlights were ‘HOT TO GO’ and ‘After Midnight’, the latter of which had been my favourite of her songs since Molly first introduced me to her. The crowd could’ve danced more, and sung a little less loud, but it was nice to dance and to take pictures to put in the album.

5/10/24

Leave a comment