I’ve loved the views from many windows throughout my life, but there are a few that have fixed themselves in my memory and crystallised as if what they contained was itself an expression of that particular period in my life.

That these windows have come to make a lasting impact on me did not come as a shock: for all of the views I describe in this post, I had a strong sense at the time, when they were still an ongoing anchor point in my everyday life, that they would go on to stand in for the way my life was shaping up.

Of course, living alongside a window, watching the viewscape grow, flourish and retreat beside you over the course of a year or longer, you develop a different kind of relationship to it than you do to one you visit only fleetingly. Perhaps the viewing deck of a tall, art deco building, or from the top floor of a stately home overlooking some austere French gardens: they can be beautiful and affecting at the time but seldom take on the shape of a life.

This much is obvious. The usual crap about how at a window you not only negotiate your own place within your town or city, but reassert the relationship between the interiority of your life and the exteriority of your life. The way you see and are seen. The way society sees you. Those paintings of women looking out of windows.

That kind of negotiation is, I think, particularly omnipresent in the lives of trans people, especially those who recently went through their transition, and are still working through what their shifting space within the wider world might mean.

I remember, some days in my youth, looking out the window as if my aspirations, the very footprint of my world, it’s stresses and sadnesses, but also its very highest peaks, were imprinted upon the tiles, bricks and blue of the sky.

In this post, I want to take a look at three windows from my life, the views within them, and how they shaped me.

WINDOW 1: THE FAMILY HOME

The first is in the old creaky Georgian building in which I grew up. From the age of 11 to 18, and then periodically until the age of 21, I occupied a third floor room of the rickety, red bricked house in which my father had grown up.

My house was in the middle of town, so there was always something going on from my window. Especially at night- I remember being awoken by shouting and drunkenness in the early hours of Saturday and Sunday mornings, sometimes watching someone being arrested and thrown into the back of a police van, sitting scandalised beside my younger brother.

In summers, when the fair came, I’d watch as rides were erected along the street, many right outside my house. Over the weekend that followed, the street would be illuminated with flashing lights, laughter and carnival floats late into the night. I have one very vivid memory of when a particularly impressive ride happened to be right outside of my house – one that swung you high up and upside down. I remember sitting in that ride, high up and upside down, for one brief moment being level with the windowsill of my third floor bedroom window- and looking back at my room’s window from the outside. I remember thinking how weird, and surreal, of an experience this was.

Then, on Tuesday mornings, I’d watch as all the rides were slowly taken down, packed up, and driven on to the next town.

I had a very different relationship to the outside back then. I thought little, if at all about my appearance, how I looked to the outside world. I just wore my clothes, and rarely looked in mirrors. I had little, if any sense of how I appeared, only wanting, like many teenagers, to blend in. Later, as I grew older, I wore wackier clothes, like some blue leather shoes with purple laces I used to wear to Sixth Form, and pale blue blazers and ties.

When I walked through town, I felt pretty invisible, which I liked. Though, I could be recognised, and would see the same people on the streets day in and day out. From a young age, I’d always aspired to live somewhere that no one recognised me, seeing a metropolitan anonymity as most conducive to a happy life. I still think much the same along these lines, though I mention this here to say that, walking the streets then, I wanted to disappear.

The view from my teenage bedroom window encompassed the centre of town, a couple of Indian restaurants, a chip shop, the town library and one of the many local pubs. From the third floor, I could see much of the rooftops of the buildings, which were generally squatter and flat roofed, and further out to the trees and hills that surrounded the town, which lay in the centre of a shallow valley.

I’d look out the window, over to the distant hills, watching them quiver under the summer heat, and dream of moving to a big city, as if then my life could finally begin.

This was the window that has gone through the greatest number of shifts throughout my life. I mean, I lived there for 10 years, so it makes sense.

I remember the first time I opened Grindr when I was around 18 in that town, and how the attention I got on that app, oftentimes from older, local men, made me think so differently about the people I saw walking up the streets. How, in this old and heterosexual town, there were older men, who had designs upon me, and the sense of seediness that brought to the town I’d always knew.

I see the view from this window only a few times a year nowadays. Looking back, I think that the last time that this window truly represented home for me was during the covid lockdowns, when myself and many of my friends were abruptly forced to remain at home with our families instead of heading back to our lives at university.

In APRIL 2020, trapped at home in an unusually warm spring, I found myself once again staring out my window, watching the movements along the street. People queued outside the chip shop, 2 metres apart. Cars drove up to the pavements and then promptly hurried off. I decided to get my camera out.

One Monday evening, early into the first covid lockdown, I recorded what became my fullest exploration of what the life beyond that bedroom window was like.

Monday Evening, Street, was a video that I made, edited and uploaded to YouTube as a way to pass the time. But I was also fascinated by what I saw. Having spent a period of my life away from home by now, the view and everything in that house had taken an elegiac feel. The way the light faded out the back of the house in the evenings, the way the light glanced off crockery and pots, the smell of the grass and the flowers in the heat.

The video is still on YouTube. I think more than anything what I was interested by was the way my bringing the camera to my usual view changed my relationship to it, and made all the trivial happenings outside my window seem fixed and certain and meaningful. I liked the mix of the sense of freedom and easiness, brought about by the burst of warm weather, alongside the profound repression of the lockdown. How that made for a laziness, an otherworldly quality, and the vague uncertainties in the people’s movements.

That was the closest attention I think I ever paid to that window, and the closest I ever will. When I go back now, I still glance through the panes, but rarely stare.

I’ve said for a while now that every time I return to my childhood town it becomes more abstract: details recede and fade into blocks of smooth colour- pale greys and browns with a bright blue oblong of sky. In a few years, that town long behind me, I like to think that one day I will return to it and for it to look like a total abstraction of colour and shape, like a Rothko painting.

I watched the world through that window, and dreamed for better one. I knew so little back then, as a teenager, and wanted so much more, but that’s not to mean I didn’t romanticise that view. I took countless pictures.

I think I always knew that my coming out as trans would signal this place, this view and this town, no longer being home.

WINDOW 2: MAGDALENE COLLEGE

But that separation started sooner. I am very much of the opinion that, from the first day I left home for university, my home would never be the same again. That view, the one from my bedroom window, would never quite be home.

The second window I want to write about is the one from my third year bedroom in Magdalene College, where I completed my undergrad degree. My third year began in 2020 and finished in 2021, and in many ways represented the end of that chapter of my life.

At the time, though, it felt like things were getting going again. Covid was mostly over, and things felt freer again, like we could resume our lives and I could maybe feel something of the freedom I’d felt in my first year.

The view from my third floor window in Benson D encompassed ‘the village’, which was the area of college specifically allocated to accommodation. I had a view right up the main walkway, and scoping from Malory blocks on the left side over to the river and the ‘beach’ on the right.

Since I’d moved to Cambridge, I’d always knew that my dream room would be in Benson block, facing back into the village. There was nowhere more central. All my friends nearby, my best friend just across the hall. The building itself was beautiful- red brick. And it was the same building where I’d spent my, generally very happy, first year of university, where I’d first tasted the freedom of adulthood.

But things were much more difficult than they had been in that first year. By this point I had already repressed the idea that I was trans, and tried to go on living in spite of it.

All this time it quite literally felt like there was something buzzing in the background, a discomfort, a disconnection, something so huge that everything, all conversations, no matter how trivial or deep, happened around it. Like I was tiptoeing around a huge balloon, navigating my life around its margins, desperately pretending that the balloon wasn’t there at all, and that the space it occupied wasn’t anything of consequence. At the time, I would’ve seen that space as the hole into which all signification, all meaning, falls away. I was a fervent poststructuralist during those days, I think, because I too was navigating a great big hole, a nothingness around which everything else seemed to flash and make sense, but only fleetingly.

I lived with great intensity in spite of that fact of my transness, which I’d discovered as a teenager. Telling myself, no, I’m not trans, that would be too authentic and sincere, I am something quite different: a gay man who believes in irony, and artifice, and the loss of signification, and the way things never quite fit together.

Of the view from my window, what I loved most was the red roof of the college, set against the blue sky. From the first time I saw it, I loved my two windows, the way they opened out onto Magdalene College proper, and the fresh, short clipped lawns of the village. It certainly wasn’t the happiest place I lived while in Cambridge- that was my first year room, which I described in detail in Reading 7, but it was certainly the prettiest, most representative view.

Like my dreams of the future, it was all brightness and air, with little solidity or specificity.

I was always fascinated by the story in Proust where a character becomes obsessed with a yellow patch of rooftop in Vermeer’s View of Delft. This was the kind of artistic ecstasy I held higher than anything else: the idea of being so overcome by a colour, type of light or a feeling that it overtakes everything else in your life. I used to hope that I would be able to feel the same thing with the red rooftops over college, and the blue sky above them.

As I wrote in a poem at the time titled ‘MANIFESTO’, “I want a red-tiled rooftop at 9am to be a very specific emotion.” This was my rooftop. And because my life meant nothing, art had to mean everything.

At the time, I was eagerly reading Sidney, especially his Arcadia, and on sunny mornings would sit by the river which ran by the side of my building. It was very beautiful, and picturesque, with the punts going by, and the light glancing through the willow trees. At Cambridge the world is very small- they call it a bubble for good reason- but I loved it there, even if I suffered so much to keep my transsexuality at bay. I hoped for the future, and read I remember, Joe Brainard. Things were very beautiful, and materially easy.

When I finished my exams that year, in JUNE 2021 the main thing I remember is the sky over Cambridge being an intense electric blue. We sat on the lawn outside Kings College, something we’d never normally do, and ate slices of pizza, taking in what the next few weeks of hedonistic drinking and revelry might ensue. And it was a brilliant summer, even if I knew that, even then, it would be the end of my life, and that feeling of absolutely safety and security I had had.

When I’d first moved to university I’d found a new freedom in walking at night. With no parents to question my activities, on evenings I would put my earphones in and wander into Cambridge, walking through town, past Kings College, and, oftentimes, to the Fitzwilliam Museum. Sometimes, on particularly empty nights, I would buy a fast food dinner on the way back and eat it in my room.

It was incredible, I thought, to have such a freedom: to be able to walk around such a beautiful city, at night, when there was nothing else I needed to be doing. I was walking, purely for pleasure. I imagined myself as a dark shape walking through the city, no one recognising me, and I loved the feeling.

Throughout my time through Cambridge, I would continue this tradition of nighttime walks, wandering through the bleak expanse of Parker’s Piece at night, with the bright streetlights casting a line through the centre of the park. Cambridge was a place that very much felt at my fingertips, and I felt untouchable, in a way.

I had a newfound anonymity that itself felt like a great power. I had dreamed that I could go mad on the mere red colour of the tiles.

On our last night in Cambridge, after spending three years together as friends, my group had a final piss up in one of our friends’ rooms. Molly and I left around 1:20am and, from my window I took one last picture of the party, that was still quietly going on across the court.

WINDOW 3: PECKHAM / CAMBERWELL

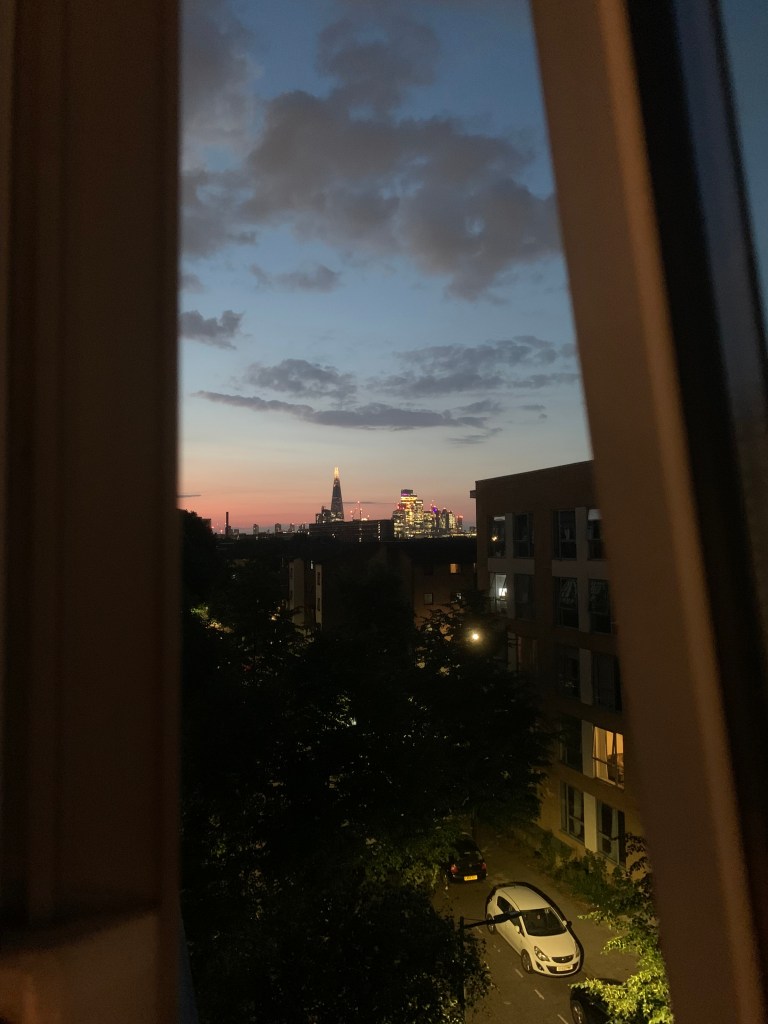

I haven’t lived here a year yet, but it’s easily one of the best rooms I’ve had, and certainly the best in London. From my bedroom window I can see straight across to the towers of Canary Wharf – and, looking left, to the Shard and skyscrapers of The City. I see them, the tall office blocks, bright and lit up at night- and think of how it would’ve set me wild as a teenager. It’s the view I always dreamed I would have.

But, of course, a window that you live next to day by day begins to fade into the background. After the first few weeks have passed, you look out of it less and less. You can spend a year, barely having paid attention to the finer details of your little view.

This is, by far, the most urban looking view I’ve had. Straight across I can see into a block of other flats. In the evenings, you can see right into their bright rooms. Sixteen year old me would be having a field day: each one is like a little Edward Hopper painting, a slice of metropolitan life stretched and flattened into a bright little tableaux.

It has been very bright and cold this January. New Year’s Eve was a lot of fun- I went to Dalston Superstore with the wonderful Molly. It was unusually warm that night, but by the first of January the warm winds had blown off and temperatures dropped.

These are the bright, wintery days I associate with winter after Christmas has passed. Now that warm, fluffy feeling of December has dissolved, the bleak blue skies can take over, and things are very clear and pristine and beautiful.

This winter, I’ve been obsessed with Bjork’s 2001 album Vespertine, which is probably my favourite winter album of all time. I adore ‘Cocoon’, which is the most haunting song about sex I’ve ever heard, as well as ‘Aurora’. The whole album has a crisp, glacial feel that reminds me a great deal of the times when it’s frosty outside and you can see the lines of ice collected on the underside of a leaf, along those little veins.

I’ve been spending more time looking out my window in these cold weeks, enjoying, in a very simple way, the feeling of looking out on a cold sky from the warmth and safety of my room.

Since moving to London, and transitioning, my relationship to the outside world has changed a lot. A part of this is because London will never feel as tangible, as manageable, as Cambridge was. It’s far too vast and ever-changing for that.

But more than this, the act of my transitioning has fundamentally changed my relationship to going outside, and being seen in the outside world. Where before I’d aspired to become invisible, and almost saw myself as such, now I feel far too visible, and spend far too much mental energy and time thinking about what others are thinking about me when I’m out and about.

I’m reminded of that brilliant line in Imogen Binnie’s novel Nevada:

That’s what it’s like to be a trans woman: never being sure who knows you’re trans or what that knowledge would even mean to them. Being on unsure, weird social footing.

I think it’s hard to overstate how much the fact of my transness colours the way I interact with the world around me, and my feeling of safety and comfort within it. A great deal of this though, is, sadly, part of being a woman. I mean, women don’t tend to go out for long walks at night- and this was a privilege I always knew I’d lose with transitioning.

As a man, especially a white one, it’s easier to feel anonymous, and invisible, like you can go anywhere or do anything and no one will batt an eye.

It’s the classic shift from feeling like the viewer to the viewed, the subject to the object. I spend far too much time thinking that people are staring at me, looking at me up and down. Many times erroneously, I know for a fact, but you never know for certain, and the uncertainty’s enough.

It gets to me, a lot, especially when I feel like I’ve been misgendered, though nowadays if I do get misgendered, it’s something I half heard, and I’m uncertain of whether it was even directed at me at all. Ah the mind games of being a trans woman. I’ve read stories from trans women who literally completely pass 100% of the time, and they still feel like people are clocking them constantly, so I’m not alone I guess.

If we weren’t living in a time of anti trans moral panic, I think I’d be less like this, but just knowing that some people are indeed out to get you makes you think everyone is. And then you’re on defensive, everyone hostile until proven friendly.

That’s the game: be a trans woman, don’t pass, and be a huge target, pass, and be less of a target, but still a target nonetheless.

High up, again on the third floor (what is it with me and living on the third floor?!) I feel a freedom similar to the one I used to feel. Though I know that my relationship to the streets that surround me is forever changed, forever made more uncertain, less secure.

My life is very happy, with this view, in London. I see my hopes for the future etched across the sky, in the shapes of the clouds that curve around the buildings, and the sun that glints off the panels of glass. But sometimes I miss the anonymity, the safety, the privilege, I once had to walk at night, to be viewer but never viewed. Even if, in almost every other way, I am so much happier, and more real, than before.

I remember, around the age of sixteen when I first read an often quoted paragraph by Sylvia Plath, and how much it affected me. Especially considering the romanticised version of male anonymity she writes of was something I looked up to, too:

“Yes, my consuming desire to mingle with road crews, sailors and soldiers, bar room regulars–to be a part of a scene, anonymous, listening, recording–all is spoiled by the fact that I am a girl, a female always in danger of assault and battery. My consuming interest in men and their lives is often misconstrued as a desire to seduce them, or as an invitation to intimacy. Yet, God, I want to talk to everybody I can as deeply as I can. I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night…”

It’s a brilliant piece of writing, but it also retains its truth, even if women’s freedoms in society have come on a long way since then. Walking freely at night is perhaps one of the most tangible things I’ve given up in order to live as myself.

But I still have my window, even if I’ve lost the privileges of feeling like a bodiless viewer.

When I’m home, and safe, and myself, I love looking out, at the trees when they’re bright and full in the summer, and the couples cooking dinner in the flats opposite, and, in the evenings, the lights from the office blocks glittering in the distance.

18/1/25

Leave a comment