it was winding, trailing, the shadows filling up the forest on a June evening, I was reading that, reading it with a falling for summer which is always long ago and far away. even in childhood it never came, it was a fairytale, something to look back on.

-Beverly Dahlen, A Reading

I swear it’s not just that I saw Barbie this week. I had this one planned before. Beverly Dahlen’s serial prose-poem(?) ‘A Reading‘, gives my blog much of its techniques, as well as its concept of a ‘reading’ as a reclamation of textual agency from dominant cisheteropatriarchal culture. Finally, on my sixth reading, I can properly introduce it.

Dahlen began writing ‘A Reading’ in 1978 and has continued to publish new volumes of the poem in the decades since, earning it the moniker of an ‘interminable work’- one that will never be finished or complete.

I personally connected with this concept very quickly- I came cross Dahlen’s poem when I was researching radical feminist poetics during my MA in late 2021. At this time in my life I was only beginning to challenge and reinterpret the history of my life that I had told myself prior to accpeting my own trans identity.

This was a gruelling time of reinterpretation, going back and forth, agonising. If anything, even now, I only learn more each day about how good I had become at self-policing my own desires, stifling them, interpreting them in more respectable cis ways, convincing myself that they were normal. So, the concept of creating a ‘reading’ of my own life and experiences that rejects the dominant narratives that make it imperative that we must be cis, is very enticing to me indeed.

From the beginning, Dahlen positions her reading within the patriarchal context of Freudian psychoanalysis, opening what was to become the endless poem with the lines:

A reading, then, of my life; or, my life as a text in relation to other texts. A translation. A kind of journal, a recurrence of days. An echo, or echos, paraphrases, quotations, a rummaging through books, songs, the speech of those around me, myself in speech, A rumination. An attempt at self-analysis, clearly against Freud’s dictum.

Freud’s prohibition of self-analysis, the concept that there must always be a (cis, male, objective) psychoanalyst present in any and all psychoanalytical readings is the first principal Dahlen rejects, choosing instead to piece together her past autonomously in order to divine new, productive meanings from it.

Of course, the very concept of a ‘reading’ within women’s studies carries with it the undertone of divining or reading signs; a hermeneutics from the margins, of undersides and revisionary histories.

So, that’s what I want this blog to do to the hackneyed, adhoc self conception that I constructed and nurtured from ages 12-21 in order to maintain the phantasm of my own cisness. A translation.

But, in this post I want to talk about something very specific that I thought about an awful lot in the year I decided to transition: the reality that, in waiting until the age of 21 to start transitioning I sorta wasted all the best years of my life.

I didn’t get to live as a girl, be a teenager, do all the normal things girls do growing up. I missed out on so much, and instead I got an adolescence and early adulthood marked by intense discomfort, emotional distance, an inability to actually truly enjoy anything, and a pervasive feeling that, especially in the most important moments, everything was very wrong.

I feel it less nowadays. But it still happens. Maybe when I see some fashion trend from 2014 on TikTok that I never got to do. It makes me think of what I lost. Going to parties (I remember aged 15 literally cancelling coming to the best party I had ever gotten invited to because I couldn’t bring myself to pull a smart shirt from my wardrobe). Learning how to do make-up. Date as a girl. The list is endless.

It’s a kind of existential pain. It’s the feeling that I wasted what Fitzgerald calls in The Great Gatsby ‘the most poignant moments of night and life’. Indeed, this quotation always stood out to me: it seemed to explain exactly why I liked Edward Hopper’s paintings so obsessively. They were about missing out, wasting time.

I know that so far I’ve generally mentioned very material aspects of the things I missed out on: make up, clothes, getting to be the princess as a kid. But these things are only really stand-ins for the fact that I lived a life robbed of joy. I didn’t get to do so many of the things that I wanted. And a lot of the things I could do felt utterly, viscerally, wrong.

It is my firm belief that our emotional lives are shaped by externality just as much as what goes on in our head. As an example, since puberty I don’t think I experienced ‘fun’ or ‘joy’ until I began to transition and was able to see myself as female. I don’t think I could feel joy until I could run back into my room and leap on to the bed in tights, smiling.

I keep wanting to rewrite these lines because I never feel like I can express this accurately. It’s something like: I did not have the capacity to experience joy or pleasure because I did not know how to understand it or express it within the tools I’d been given. It didn’t feel natural

This idea of missing out on all the aspects of growing up female so coloured my psychic life that it can be seen almost everywhere in the projects and pieces of writing I put all my time and energy into growing up.

In my first serious piece of writing from 2017, frseeeeeeeefronnnng, named after the sounds made by trains running past Molly Bloom’s house as she lays in bed next to her husband in the concluding episode of Ulysses, I wrote a revisionary history of my life in which I existed as two intercrossing entities: a boy and a girl. They’re given no names beyond ‘boy’ and ‘girl’, ‘he’ and ‘she’.

The boy, who the narrative follows, is about to go to study law at university, is emotionally repressed, closed off to new experiences, unable to experience the world directly. He is panicking about having to go into the world, to study law, and there is the feeling that everything is wrong for him.

The girl, who he meets skulking in the bars of San Francisco, is a socially liberated, arty type, reads Walt Whitman, looks suspiciously like Emma Stone from La La Land and writes poetry, drinks whiskey and travels the world. She is able to act just as she wants, and is unselfconsciously feminine. He is nothing, he is the absence of characteristics. Even when I wrote it aged 17, this was how I imagined them.

In this story, San Francisco is a backdrop of absolute beauty and delight, filled with sights and sounds, none of which are open to him as he sits in a bar or excessively clean hotel room, looking out windows, Hopperesque.

Until they meet, he is one of Hopper’s male figures, wasting ‘the most poignant moments of night and life’. They meet and she changes his life forever (definite manic pixie dream girl trope here but like yeah apologies I was 17). She shows him what liberation means, and, it is clear that her life as a woman is very integral to this.

At the end of the story she disappears and he’s left in a crowd of people at San Francisco airport, newly aware of all the things he’s missing out on.

The story ends with him repeating a line he must’ve read when she handed him her book of Whitman poems: ‘Shall we stick by each other as long as we live?’ The classic bittersweet ending, just the sorta stuff I ate up at that age.

Looking back, it’s hard not to see this story as me grasping with both all that I had missed out on so far as a man, and me grappling with the future I had in front of me. The boy is clearly at a turning point in his life, he is just about to go off to university, and throughout the story he is faced with the question of whether to go on as he is and remain distant, unreal, or live like the girl.

Just like the ‘frseeeeeeeefronnnng’ Molly Bloom hears from the passing night-trains, this story is about the world going on outside, and all that I missed out on. It’s about the fairytale, all that I missed, and continued to miss out on, for four more years:

it was winding, trailing, the shadows filling up the forest on a June evening…

The other piece of writing that was truly all-consuming for me was Sunset Sex with Bailey Jay, a long poem in which I try discover the edges between myself and Bailey’s psyches. In many ways, it was an attempt to understand where I stood in relation to her transness.

I did so much research for this project. Speaking to Bailey- who was by now a friend of mine- on snapchat, spending so much time messaging her, asking questions, us finding out together about the old house she grew up in, its built environment in Richmond, VA. I imagined how she grew up as a trans girl and what type of adolescence that would entail. She showed me on Google Maps the 7-Eleven where she bought her first make-up.

Like all things to do with the women I was crazy about, I thought this all sounded fantastic, beautiful, totally out of reach to me. The poem, which I began aged 18 and finished aged 20, passes through a drug-infused maze of platitudes and realisations, tracing the route of my obsession with her, trying to figure out why she was so significant and transformative for me, before reaching what I saw as the poem’s biggest message:

And I know she’s sitting by the pool

Late on a warm February afternoon.

I can hear cars in the background.

Metropolitan areas. So we can’t know the whole

Secret from beginning to end. Otherwise the rest would shift

Accordingly. So there is only awareness of things other.

And it goes on and on like this until you say

“I certainly missed out on a lot of stuff.”

Missing out, it seemed, was the final revelation. The thing I was to learn from all this. I can hear cars in the background. frseeeeeeeefronnnng. These things are going on without me.

This is how I tend to mentally characterise my teens and early adulthood: I felt like there was something wrong with me, like there was something deeply unpleasant about my body which other women didn’t have. Like I didn’t deserve to love or be loved, but could enjoy it in abstraction, through glances and undersides and fantasies. I could hear it at night.

A lot of trans people talk about feeling like they lost their childhoods. The idea appears everywhere, and, while it’s obviously very sad, it’s a nice additive to the general conception amongst cis people that dysphoria is about genitals. I mean it sorta is, but like, no not really not at all. The reason cis people assume this is because in most cases they cannot imagine what it would be like to live in the wrong gender. They can’t imagine how it could feel, or how it could curtail – stifle – steal.

It is this feeling, the feeling of the fairytale that happened but didn’t, that was felt but indirectly, that animates things like Dylan’s Mulvaney’s ’xx days as a girl’ series. Like many trans people, Mulvaney is attempting to reconstruct a lost childhood and adolescence by projecting it into the future.

It’s the pain that animates Imogen Binnie’s Nevada and Maria’s inability to convince James, whom she sees as an egg version of herself pretransition, transition sooner than he is ready to. It’s like banging on glass and saying please, please realise it before I lose any more.

You can see this loss manifested in Nicola Dinan’s superb novel Bellies, published this year, when Ming goes to the trans support group:

I survey the room from the side, and note once more how most of the people at support group have fallen into the Great Regression, the involuntary rewind of speech and behaviour when a person transitions, the deep psychological urge to relive youth which prejudice and self-loathing stole from them. They’re trans in the psychosomatic sense, but also trans in that they’re teenagers stuck in the bodies of adults. I’m grateful to have mostly escaped it. (p. 140)

This kind of thing is particularly sad when someone transitioned later in life, 30s or later. Everyone has their own time to do things, but it must be hard. I’m so lucky to be able to even get some of my twenties. Dinan writes later:

It’s not so much dying that scares me, but dying young, because in a lot of ways life has only just begun to feel like it’s worth living. I’m catching up. (p. 192)

It’s exactly this. Dinan’s novel is fucking incredible- immediately my favourite trans novel- and I shall devote a whole post to it soon.

I think all of the ways people use to deal with this particularly invasive form of dysphoria are totally valid. But, I’m reluctant to accept for myself some of the methods that people like Mulvaney use. I’m loath to try to relive my lost childhood and adolescence. If a cis childhood is what I wanted, I’ve already lost it. I don’t like the idea of trying to do it all now. It feels too forced, too artificial, too palliative. I’d be playing ‘catch up’ the rest of my life.

In fact, I’ve come to accept that my trans-girlhood existed the whole time. It ran parallel like rails: that’s what I was hearing. That’s why I’ve been writing things like Readings 4 and 5, trying to outline how my girlhood existed, even if stifled by the prejudice and self loathing Dinan describes.

And, of course, the fairytale of ‘girlhood’ is a very particular and wholly idealised construction, inflected with whiteness, classism. It ignores the misogyny I would’ve faced growing up as a girl. It ignores how suffocating girlhood might feel like to trans men, gender nonconforming lesbians, nb people, and others. It ignores so much.

Accepting this doesn’t stop the pain, but it’s important to recognise the ways in which the collective childhood we, as trans people, lost never really existed, as much as it hurts me to imagine all the very real, very material things I missed out on:

even in childhood it never came, it was a fairytale, something to look back on.

I work in marketing for schools, and came across a lot of summer prom posts from our schools during July. It made me remember my own Yr11 prom. It was me and my friend Amy, both of us pretransition, both wearing suits we hated, stood in my garden drinking as much alcohol as we could before getting driven to what was supposed to be the best night of the year.

I remember the sensation of the fierce sunlight on us as we stood there blinking in our dark suits, my grandma and mother taking pictures of us with the flash on. I remember feeling blinded by the light in the garden as if the sun itself was that one camera flash continuously reiterated. Like that one exposure had become indefinite.

We arrived wasted, presumably drowning out what we were missing out on. I remember countless moments like this, but I also remember so many little pockets of joy and excitement.

Like when I got my first girlfriend in year two and spent that afternoon on the playground hanging around with all her girl friends and trying to be like them but not really fitting in. And going home and watching Bratz on TV because I had a girlfriend and needed to be just like her and that was normal!

Or when I was in year 1 and this older girl called Chloe who I looked up to kissed me on my cheek and I felt like she had transferred something to me- something that would make me less wrong- something that would make me just like her. That was how I thought, and in some ways I haven’t really outgrown this either.

Or me excitedly explaining what female puberty was going to be like to some of my girl friends after hearing about it in year 6 sex ed, not quite clocking that it wasn’t going to happen to me.

Or my new bright pink and blue Slamm scooter while I rode around town with my long hair. And the freedom I had as a kid, running around my house in my huge Stella Artois T shirt which I wore as a dress.

There are many more instances, these just spring to mind. So, while I missed out on a fuck tonne of girly stuff and I spent a lot of years in turmoil, hating everything and hating myself, I do also believe that I did get a transgirlhood.

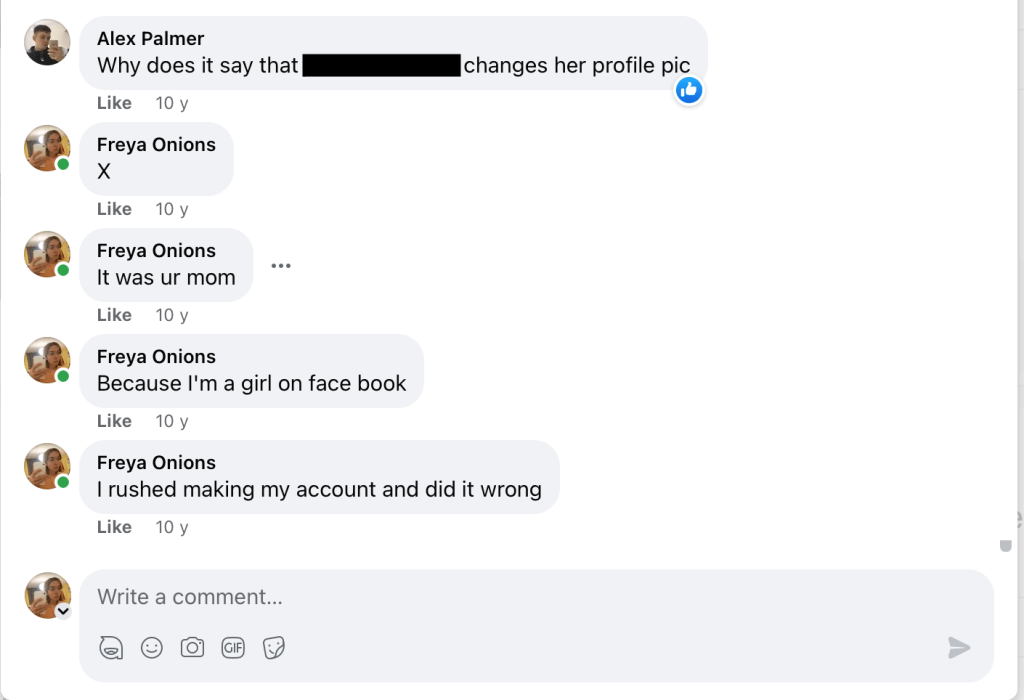

A really interesting encapsulation of what I mean here happened just this week when I went through my old Facebook posts on my wall. One post from 2012 in which I updated my profile picture was followed by this series of comments:

‘Rushed’. lol. I don’t actually remember whether I intentionally picked to be a girl on Facebook or not, but this exchange was so enlightening for me to find because of the revisionist history of my childhood it offered.

According to this conversation, even then, I was ‘Freya Onions’. Even though, back then, I was living as a boy, the Freya I became 10 years later, is dropped straight into that reality. According to Facebook’s archive, I was Freya even then.

This explains a whole lot. It explains the joy I felt when I was in love with Alex and ran home from the churchyard park smiling. It explains why for whatever reason that feeling felt sorta girly when I got home. It explains why my initial response to his question was simply a kiss (X).

It felt good to read this old conversation in this new way, with the context I now know. It showed me another instance of my childhood lived authentically, where I actually felt real, even if this was brief.

I’m glad I don’t have to go back and forth anymore. I love the stability I feel. I now see it as an absolute privilege that I can have normal problems. Normal problems with love, or money, or work. It all feels so easy compared to the turmoil I felt.

That fairytale was always something that was already lost, even in childhood it never came. But that life ran parallel to me like a streetlight, and, in precious moments, I felt it.

This will not be the last time I discuss this topic on here, because I have a lot more to say about it- and expect to hear more about Bellies and Nevada as well. This past week I’ve been dancing around my room to Tyler the Creator’s IGOR in a way I never could’ve as a teen- back when I fiercely hated the concept of being seen doing anything, especially experiencing pleasure or joy.

Everything can feel so different, but looking at my past like this helps me feel a sense of continuity and completeness.

I dance with my little green earphones in and catch a glance in the mirror. I have girl hair now. I love that.

29/07/23

Leave a comment