It comes and goes; the walls, like veils, are never the same,

Yet the thirst remains identical, always to be entertained

And marvelled at. – John Ashbery

Yesterday I finally got round to exporting and downloading the 5 years of ‘memories’ that had been ominously sitting in Snapchat’s unlimited cloud storage. I’d been putting this off for many years: my saved snaps are so voluminous that I knew such an endeavour would take many hours, and I was reluctant to accept that the process of downloading them strips the images of the metadata (time, date, etc.) that, in my opinion, often brings them into contextual and narrative life.

Anyway, I did it. It took 5 or 6 hours of fiddling, the bloated app crashing every few minutes or so from the sheer effort.

It had to be done: Snapchat passed its peak in the Zeitgeist many years ago, and I figure it is only a matter of time before the vastly generous unlimited cloud storage they offer for saved snaps disappears. Footprints in the sand.

Seeing as my photos, both those Snapchat and saved on my phone are easily my most prized possessions- important beyond anything physical I own- I knew downloading them so that Snapchat couldn’t fuck them up or lose them was of absolutely vital importance:

Contained within my Snapchat memories is the full story of my life from 2018 up until the present moment- over 3,000 photos and videos- that show me going from dazed boy obsessed with transsexuality starting university, to making new friends, to moving to London and transitioning myself.

Together, those photographs, while not escaping mediation as Snapchat’s name ‘memories’ likes to imply, serve to create an interconnected web of signifiers that gesture towards the memories in my mind as they fade, distort, take on new significances, or fade into obscurity. Looking through those photos, I do not relive my life as one might do with memory, but I reread it. I reinterpret it.

Going through my life, month by month: in many ways it was similar to the project I’ve been working on with this blog for the past year or so- namely, reassessing my life through various memories and reassembling those remembrances and confusions in and through the transfeminine identity I have come to accept as my own.

Read through this identity, as I have suggested elsewhere, my memories tend to make a heck of a lot more sense.

It felt very apt to be undertaking this task on the 1st of September- for me at least, the end of summer has always been a time of reflection and reassessment- often in a desperate attempt to reconstruct the sense of self I watched crumble away in the summer weeks beforehand (see Reading 7). Not only this, but it reminded me of another time in my life- the first time I made an attempt to download all my Snapchat memories, which was in late August of 2021.

This was the summer of my graduation from Cambridge. As a last send off with us all together my friendship group had arranged to spend a week in Canterbury. We rented a big townhouse and got drunk every day. Midway through the week, on the morning my friend broke the others’ jaw in two places, I ran downstairs and chucked my clothes in the washing machine, forgetting that my phone was in the pocket of my pyjama shorts.

I realised around 5 minutes into the wash, running back down 2 flights of stairs again to the machine churning in the kitchen. At first the phone seemed to be working fine, though the screen was a little fucked. Seeing as the iPhone 7 was supposed to be reasonably water resistant, I sorta thought I had gotten away with it.

Then the phone began to deteriorate. I took it to a repair man in Canterbury but he wasn’t any help. I returned the dead phone to my bag and waited until the end of the holiday for it to- hopefully- dry out.

Over those days the enormity of what had happened- the catastrophic results of an act as simple as 5 minutes in the washing machine- began to hit me. Saved on my phone, which I had had since 2017, were 5 years of un-backed up photos. My whole life.

I still had my Snapchat memories, yes, but they had no metadata, and were only half the story. Not to mention, they started in late 2018, missing the whole of 2017 and my last years at school.

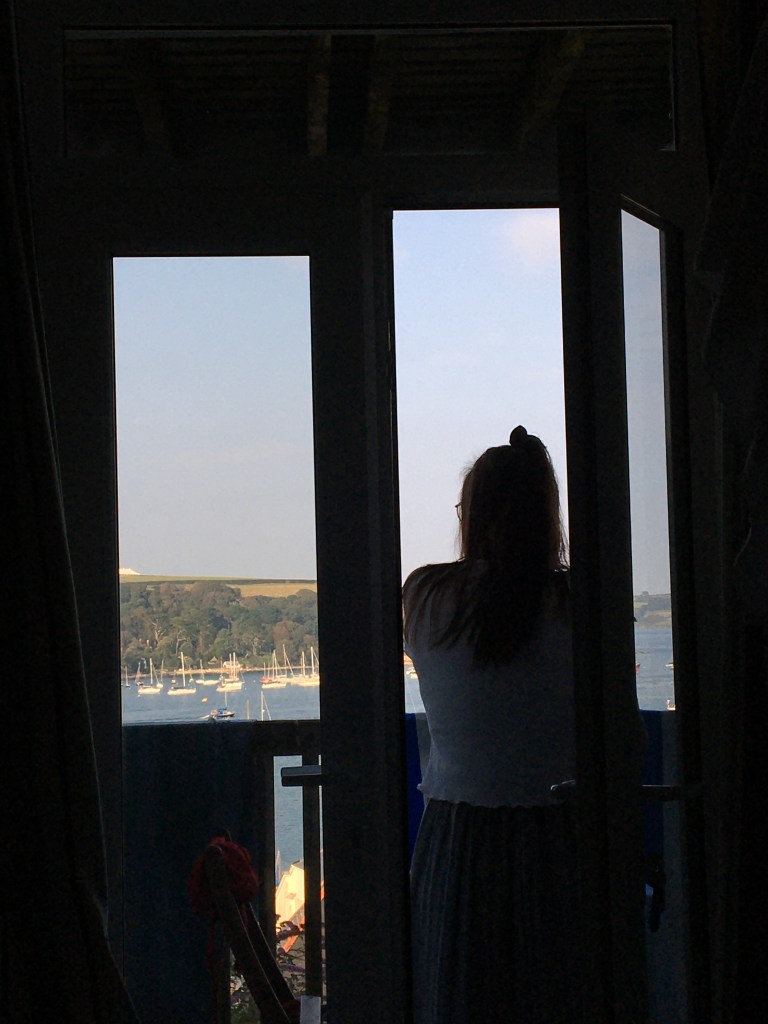

At the end of the week, Molly and I got the train from Kent to Falmouth in Cornwall to continue the holidaying. I tried to turn the phone on but it was by now clear that it was fucked. We sat in the Falmouth Wetherspoons at 10am and I went into crisis mode.

I ordered a strong cider, wanting to take the edge off. My whole life, my whole late adolescence and early adulthood- its documentation- the proof that it happened- was disappearing.

And the timing couldn’t have been any worse. Finishing university can cause an identity crisis even in those with the stablest identities. For me, this happened to also be the time when I was reluctantly beginning to accept that I am in fact trans and that my attempt to run from it for the past two years had failed miserably.

This added only another layer to the enormous sense of loss I felt. Molly sat opposite me drinking a soft drink while I tapped my foot and necked my cider.

See, a key reason why I had rejected my initial realisation that I was trans in 2019 was the threat of loss that came hand in hand with it. As I’ve mentioned before, I knew that most of my friendship group- particularly those who are the loudest, were deeply transphobic. I knew that the spectre of my transness would mean if not losing them, going through hell. The same was true with my parents- so well had I hid my transness that they would doubtless think it had come out of nowhere.

It also meant losing a load of my privilege, my employability, the invariable rights I would’ve had as a straight-passing cis white male adult. Accepting my transness meant losing almost everything, so I panicked- and rejected it.

But it also meant losing another, more intangible thing: my memories. If was was trans, and really a girl, what did that mean about my memories? What about the things I had enjoyed- my friendships? Did they now mean nothing?

Of course, this was not true. But for me it certainly was the case that accepting my transness meant having to see my past in a very, very different way. This has taken me years to do- and it’s an ongoing process.

I remember back in summer 2019 when I sat in my childhood bedroom sitting in terror with the revelation on the edge of my bed. Scanning around the room. Dark blue decorations, dark blue bedding, flannel shirts and grey jeans on the back of the chair. None of this I would’ve chosen if I had any choice. Another shudder passed through me. The whole room felt alien. A lie.

I rocked back on the bed and tried to hold back the immense feeling of sickness. The pictures of me as a boy with my family along the mantelpiece. My relationships. My old name. I’d have to throw them all out.

I will never be able to describe how overpowering this felt other than to say that it was so horrifying I had to push it all away for 2 years and lived with my teeth set, lying to myself, until August 2021.

Now, here I was again. Uni had ended, nothing had changed. I’d tried dating guys, guys I liked, but I hated it- hated being seen- hated being another guy- flinched at being touched. I felt an insurmountable evil passing through my body, unreal, and fell back behind my eyes. When I looked in the mirror no one was behind my eyes. I receded further back each time I looked.

Where accepting my transness felt like it meant losing almost everything, including the relationship I had with the friend I loved most, Molly, who sat across the table with me, here losing the photos was just the concrete manifestation of that loss. The memories going.

I had written about this idea of the revelation of transness invalidating and signalling the loss of one’s previous life in Sunset Sex With Bailey Jay all the way back in 2019:

But

If this were the case it would leave a black hole leading

From this moment all the way back

To the day I was born. If true, it’s all empty,

Misused space. Do you mind if I stick something

On the speaker?

Accepting that I was uncomfortable about nearly everything in my life surely meant that my memories, those pictures I prized the most, were now both the key to my future and the anchor holding me back from liberation. They were the lie told over and over.

Having spent a lot of the covid lockdown obsessing over Hegel I tended to think dialectically at that time: these photos- the record of my life as a boy- needed to be not negated but sublated– synthesised into a new future.

Unlike many other things in my life, they weren’t to be rejected- they were to be transformed- reknitted together. And, while I knew that I wasn’t going to be able to look at myself in them for a long time, I knew that I would need them in the future.

When Molly and I got back to the house from spoons I started frantically downloading my Snapchat pictures. No metadata. Detached, lonely signifiers.

I panicked and panicked but couldn’t tell Molly the true significance of the loss. She went back home to Devon a few days later. On the 7 hour car journey from Cornwall I tried to sit looking at the road without thinking.

Molly had gone, and as we drove up the M5, only got further away: her to live in Devon, me to move to London a month later. I loved her so much. We were to see each other far more infrequently from now on.

We continued driving and it all came flooding back. All those desires and jealousies and fears that I had tried to hide. Everything that had reared its head in 2019. I felt it like an enormous weight falling on me. It literally felt like I was being crushed.

Where in my third year of university spending all my time in close proximity with Molly had minimised my dysphoria, now I was all on my own, my hideous maleness more apparent than ever. With Molly gone I knew I couldn’t live on as I was.

We got back home and Autumn had arrived in my home town. We got out of the car and looked over the fields from the fence. Maybe 7 or 8 hot air balloons floated over the horizon. Golden hour. I knew I couldn’t run from it anymore.

So began my transition, very slowly at first. I bought women’s deodorant the next week. Baby steps. I felt utterly terrible, but sometimes one small thing can keep you going.

A while later a miraculous thing occurred: a repair shop in Codsall managed to retrieve the data, killing my phone in the process. Hurrah! From now on everything would be backed up to iCloud. Never again.

I have always thought photographically. Even as a child, I’ve always liked things in very pristine images, small things I can hold.

From the age of around 14, my first attempts at post-puberty identity construction were made possible by the photos I took the previous summer on holiday with my family in New York. That was me: I would be a traveller, off on my own in some huge city in huge sunglasses sipping a Starbucks frappe (I really liked ‘white girl stuff’ at that time).

I talked about New York all the time. I looked back at the pictures- here was a place I could live.

Me and my friend Ed started watching, and obsessing over, YouTuber Casey Neistat’s vlogs. He ran around New York with his camera with a lust for life and a hyper focussed attention to the beauty of the every day. Filming every day of his life, he found beauty and meaning everywhere. I started looking at everything around me anew.

In January 2015 I used my Christmas money to buy a Canon camera with a zoom lens and it changed my life. I took it on walks around the frosty garden, out into the fields around town, finding new significance everywhere.

Of course, these photos were generally landscapes. They very rarely included people, and definitely not me. One thing was certain, if I was going to create my utopia, my dream life, it certainly wasn’t going to include me.

I took pictures everywhere, coveting them, honing my eye. If I wasn’t to have a body, I could certainly have an eye. I would be an observer, I figured- floating arms without a torso.

I signed up to travel magazines, collected travel books, and spent endless hours looking at glossy images of beautiful places without me in them. I saw the camera as a kind of bodiless room: the word itself having some kind of etymological root in the concept of a ‘room’, an empty space. Finally, here was somewhere I could be.

For this life to work, I would have to be always be on the move. A passerby.

When I wrote a letter to my mother coming out as trans I explained my gender like so:

The one way I can think of describing the lack of ‘presence’ I am associating with living my life as a man is by likening it the viewer of a painting that uses linear perspective. The viewer/ painter is a recorder and an observer – present (in some senses) in the scene but at the same time disembodied. The sitter in a Vermeer couldn’t speak to the artist as he painted- he was absent behind the eyes, which functioned like a camera.

The camera has been my empty room- a place where I could live my life in retrospect, without ever having to be there myself. Because, if I had had to be there I would have to be there in my body, in men’s clothes, acting masculine, be the ‘boyfriend’, to be ‘he’, and hide all the jealously I felt towards the women who got to do everything I couldn’t.

This was why I fell in love with Plato when I was 17. I always wanted to sit in a dark box with chinks of light coming through. That was my dream, but it was also my reality.

In most cases, under the Platonic metaphor, the chinks of lights were little images- memories or pictures that made my existence bearable. Maybe 10 or so images of Emma Stone, the actor I was obsessed with. Or a picture Bailey sent me over Snapchat. I lay under the memory of them as under a streetlight, and shuddered a little less.

I even remember when I was 9 years old and for a short time kept an image of Miranda Cosgrove from iCarly that I had printed in my little green backpack.

Obviously things couldn’t go on like this forever. I knew had to leave the dark room. I wrote about this concept several times in my projects of my late teens and early 20s:

I hear all this nonsense everyday,

Along with other whispers from the dark room where meaning is Constructed. (Sunset Sex With Bailey Jay, 2020)

Shut up, I only do unrequited love. Thou art translated:

‘Camera’ means ‘room’. And for years the room is empty. There is no body there. Incidentally ‘stanza’ also means ‘room’, many of which also stand dormant and faintly absurd, like a stopped clock.

(Swimming Pool, Tennis Court, 2021)

Looking back at how I was feeling when I wrote these reminds me of why A Wave (1985) by John Ashbery is still my favourite long poem, and why its climax still stands as one of the most affecting stanzas I have ever read:

And though that other question that I asked and can’t

Remember any more is going to move still farther upward, casting

Its shadow enormously over where I remain, I can’t see it.

Enough to know that I shall have answered for myself soon,

Be led away for further questioning and later returned

To the amazingly quiet room in which all my life has been spent.

It comes and goes; the walls, like veils, are never the same,

Yet the thirst remains identical, always to be entertained

and marvelled at. And it is finally we who break it off,

Speed the departing guest, lest any question remain

Unasked, and thereby unanswered. Please, it almost

Seems to say, take me with you, I’m old enough. Exactly.

And so each of us has to remain alone, conscious of each other

Until the day when war absolves us of our differences. We’ll

Stay in touch. So they have it, all the time. But all was strange.

So I lay there on my bed downloading my Snapchat memories. For the first time since 2019 I re-listened to the incredible album You Forgot it in People by Broken Social Scene. It was pretty emotional for a few hours, then I just had to get it done.

I saw all of them: the pictures of me as a guy- the steely gazes- the nothing behind the eyes. I remember how I wanted to writhe in my clothes, how I had always associated my own masculinity with the feeling of myself sinking deeper, further back into my eyes, further back into the dark room.

A lot has changed since then. I still take lots of pictures. I still generally hate seeing myself in all but some photos- but there are at least now some that I really like.

After a recent reunion of my university friendship group I saw a few pictures of me and my friends. I saw myself there, in amongst them.

02/09/23

Leave a reply to Reading 10: On Being Here Now – Freya-Onions-report Cancel reply